What Kellogg Faculty Fellow Karen Graubart didn’t find in archives in Spain and Peru was, in some ways, as valuable as what she did.

An associate professor in the Department of History, Graubart has spent more than 15 years conducting archival research on women and non-dominant communities in the Iberian Empire for her first two books. Much of her research over the years has been supported through Kellogg Institute Faculty Grants.

But she is also considering how the archives themselves have shaped her research – by questioning who is represented in them and why.

“Indigenous women are all throughout the archives in Peru, but the archives in Spain are radically different,” Graubart said. “Women are much more hidden, and the archives of the Muslim community and the Jewish community don’t exist anymore. Part of my work is trying to figure out why these two places look so different and what that tells me.”

Graubart, who has spent this year as the Gender Studies Program’s first internal scholar-in-residence, is also bringing the issue to her graduate students this semester through a class called Archives and Power.

“Historians are generally aware that archives are more than mere repositories of information, but we don’t always think about the ways buildings and institutions guide our research,” she said. “In this class, we’re reading critiques of archives and paying special attention to the ways that archives marginalize, naturalize, or silence certain people and practices.”

Enriching the curriculum in gender studies was one of the primary goals of the scholar-in-residence position, said Mary Kearney, director of the Gender Studies Program and associate professor of film, television, and theatre.

“It’s been great having Karen as our first ISR,” Kearney said. “She has served as a wonderful mentor for Lindsey Breitwieser, our first postdoctoral fellow.

“Developing this class has also been terrific in exposing our students to how power and privilege operate in institutions whose mission is focused on knowledge and history.”

‘It all falls apart’

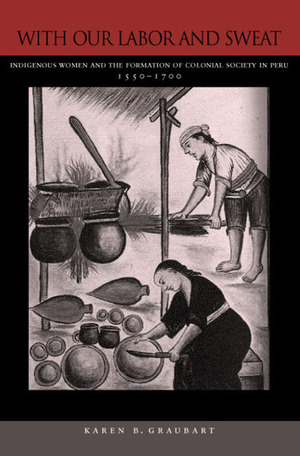

Graubart’s first book, With Our Labor and Sweat: Indigenous Women and the Formation of Colonial Society in Peru, 1550–1700 (Stanford University Press, 2007), examines the ways that indigenous women participated in, created, and adapted to the society produced by Spanish conquest in two cities in Peru.

Graubart’s first book, With Our Labor and Sweat: Indigenous Women and the Formation of Colonial Society in Peru, 1550–1700 (Stanford University Press, 2007), examines the ways that indigenous women participated in, created, and adapted to the society produced by Spanish conquest in two cities in Peru.

With support from a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship, her second book project investigates the ways that subordinate peoples – Jews, Muslims, and sub-Saharan Africans in 15th-century Seville, Spain, and indigenous and African-descent peoples in 16th-century Lima, Peru – both used and undermined notions of “difference” intended to classify and contain them.

Republics of Difference: Racial and Religious Self-Governance in the Iberian Atlantic, which will be published by Oxford University Press, specifically examines how and when the political structure enabled these groups to function as self-governing bodies – and whether people took advantage of that structure.

“While most of these non-dominant groups were allowed to self-govern, people of African descent who were enslaved in Peru were not,” said Graubart, who is an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Africana Studies. “Unlike in Seville, where they’re also enslaved, they are rarely treated as a republic. For reasons I explore in this project, it all falls apart.”

The only exceptions, she noted, are when they are able to escape to the mountains and form runaway slave communities. At that point, those of African descent are sometimes invited to come back to form a pueblo de negros or “black town” and given the same rights as the indigenous people.

“In the course of writing that book, that problem became really interesting to me,” she said. “I started thinking about these runaway slave communities that turned into towns and it became really fascinating.”

Graubart is now delving deeper into the issues facing these communities for her next book project, tentatively titled Fugitive Blackness. In it, she broadens her geographic scope to explore the issue across the circum-Caribbean.

“In places like Panama and Cartagena, Colombia, there were lots of runaway slave communities that were enormously problematic,” she said. “The crown regularly offered to turn them into towns so that they would pay tribute to the king and then police other runaway slaves. It actually delegated slave-catching to the former slaves.”

She is also exploring the topic – and its modern implications – in a seminar through Africana studies, which invites students to consider what it means that blackness is associated with fugitivity.

‘Something really special’

Last semester, Graubart co-taught another new class for the gender studies program based on her research, "The Making of the Atlantic World: Gender, Ethnicity, and Slavery," with associate professor of history and Kellogg Faculty Fellow Mariana Candido.

Last semester, Graubart co-taught another new class for the gender studies program based on her research, "The Making of the Atlantic World: Gender, Ethnicity, and Slavery," with associate professor of history and Kellogg Faculty Fellow Mariana Candido.

“Gender shows up in many interesting moments in my research,” she said, “and I’m excited to be bringing these issues to students who have a critical gender studies perspective. There is something really special about the program and the passion and the energy in it.”

Graubart, who joined the Notre Dame faculty in 2007, also co-runs two working groups through the Kellogg Institute – one on Latin American history and one on gender and slavery in the Atlantic world.

The University’s many opportunities for funding – through the Kellogg and the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, among others – and for interdisciplinary collaboration are invaluable, she said.

“Notre Dame has really just been a wonderful space for programming, for creating cohorts of graduate students and scholars, and for having these intellectual conversations,” she said. “It’s an incredibly collegial space.”

This article originally appeared at al.nd.edu.