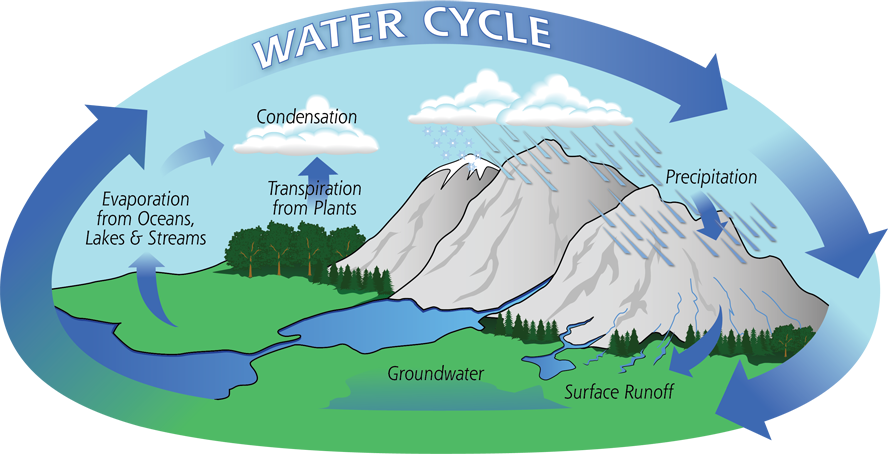

We don’t normally think about how humans influence the flow of water. Typically, how water flows has been depicted by the water cycle (see figure below). But this depiction is inaccurate because it assumes, incorrectly, that water flows independently of human influence. Around the world, conventional wisdom about the water cycle assumes that freshwater can be abstracted for multiple uses without deep understanding of, or regard for, the impact on natural regeneration and ecosystems that thrive on water.

As we have advanced technologically and exploded in population, the human impact on the water cycle has become ever more detrimental. Unaware of, or willfully oblivious to, long-term consequences, the public and private sectors dam rivers without considering the shifts caused to flow patterns, some of which exacerbate historic injustices against low-income and minority communities. In addition, human-driven climate change degrades the water cycle: shifts in rainfall patterns, for example, and rapid evaporation rates hinder the reabsorption of water into underground aquifers. Short-sighted decisions to maximize shareholder profits lead to over-extraction of water for agriculture, energy, and mining. The mounting man-made stressors on the natural water cycle have made it more difficult to track, mitigate, and resolve the global water crisis.

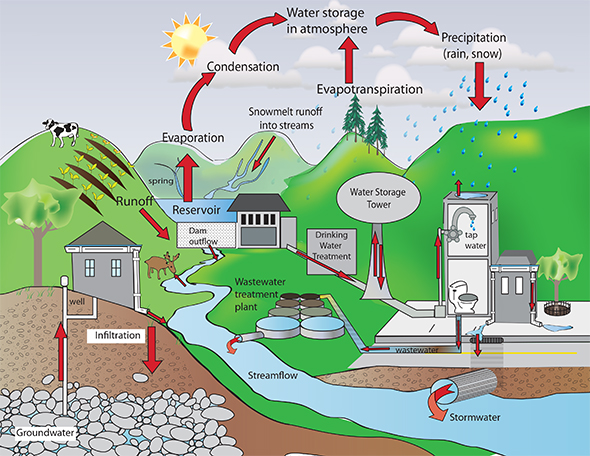

In short, economic, physical, and social decisions and mechanisms shape water availability, quality, use, and management. Relying on simplistic depictions of the water cycle glosses over these important dimensions of water. Thus the need for a new illustration of a water cycle that considers how humans interact with and influence the flow of water.

Governance perspectives dictate water management and use

Some of the most contentious debates on the management of water center on who should control water distribution, how they should do so, and how much water we should distribute for what purposes. These questions are contested because many consider water to be an unconditional human right. The United Nations Committee on Economic, Cultural and Social Rights defined the parameters of these rights, paving the way for legal frameworks to ensure them.

Although the definition of the right to water includes affordable access for personal and domestic use, the challenge is that the standards by which to measure and ensure such access typically depend on the differing perspectives held by public, private, and civil actors with competing interests and motivations. Private actors tend to prioritize profit, while public actors are often concerned primarily with affordability. Civil society actors seem focused on questions of equity—for example, how much should people be charged for drinking water, and how can tax dollars be equitably distributed to ensure water for all?

Globally since the mid-1800s, water has been managed largely by municipalities. Municipalities are often considered ideal water management entities because of their ability to achieve economies of scale and subsidize water to make it more affordable for low-income customers. Despite its potential, public water management by municipalities has failed to satisfy the water needs of all, particularly in rapidly growing urban areas in developing countries where bureaucratic red tape and corruption slows progress. As a result, alongside global economic trends like the establishment of the Washington Consensus, privately owned water management companies emerged and began increasing operations in developing economies.

Proponents of private sector water management argue that private companies have access to more diverse financing and can provide higher quality, more efficient water services. Critics point to the fact that private companies often only provide high-quality, efficient services to those who can afford elevated prices. These inequalities are important factors to consider in understanding the limits of the water cycle. While the question of whether water privatization is a worldwide failure remains debatable, it goes without saying that many of the countries that privatized their water systems in the Global South still struggle to provide water for their rapidly growing populations. Ultimately, both the public and private sectors suffer from the challenge of satisfying the human right to water while contending with shrinking freshwater resources, a growing population, and limited financial capital.

Virtual water matters too

While the global market system encourages free-flowing goods and services, the impact of consumption on global water supplies is significant. The race for development motivates countries to increase their exports in foreign exchange products like textiles, but neglects to consider how much water is used to produce them. The amount of water required for, and embedded in, the products we use, also known as virtual water, usually strains water reserves of countries trying to earn foreign exchange through exports. Ironically, even though boosting trade theoretically improves overall quality of life, it is often at the expense of adequate domestic water levels needed for drinking, sanitation, hygiene, and agriculture.

Further complicating matters is that more developed countries disproportionately consume products, burdening the Global South with demand for more virtual exports in exchange for currency. But communities cannot drink money, and therein eventually lies the rub. If we were to visualize a new type of water cycle, it would need to include global virtual water consumption patterns and their asymmetric country needs, with an indication of how what happens abroad affects people locally and vice versa.

An accurate water cycle is critical

A human-centered approach to water use and management draws attention to its value beyond physical and economic dimensions. In some cultures, water is integral to social and spiritual expression. Water shapes social interactions between communities. For Indigenous peoples, for example, water is spiritual—a sacred gift—as well as a symbol of strength and renewal.

Managing water as a solely physical resource thus threatens integral human development. Ineffective management of water expands inequalities related to access and availability of water for basic needs. Billions of people still live without adequately managed safe drinking water, sanitation, and basic hand washing facilities. Vulnerable groups like Indigenous peoples, children, and women become prone to discrimination and social immobility as water scarcity threatens local livelihoods. Understanding these mounting barriers to preserving the many dimensions of water security opens opportunities for public, private, and civil society actors to engage an integral approach toward water, understood and managed as a global commons that leaves no one behind. The myriad of dimensions of water use should be included in an updated depiction of the water cycle to emphasize the possibilities of how efficient water management can benefit society, especially the marginalized and most vulnerable whose dignity is at stake.

There is a clearer path forward

The nexus of water with other sectors cannot be overstated. Water affects the sectors of food, energy, environment, and health, to name a few. With this broader context in mind, a revised description—and assessment—of the water cycle must convey the complexities of man-made as well as natural transformations of water. It should identify the major public, private, and civil society actors behind water use and management. The new illustration should convey the reality that it takes all actors working together strategically to maintain robust water resources. An appreciation for natural yields should be incorporated to show the global impact of virtual water. Equally important is to impress upon people that man-made climate change threatens the availability of water to use for the support and flourishing of physical, economic, cultural, and spiritual life.

With a clearer illustration of the factors that complicate water use and management, solutions can become more holistic. Effective efforts to mitigate climate change, for example, must be born of a multi-dimensional understanding of the intangible values of water and the levels required to preserve it. Present-day water cycle illustrations, as noted, do not convey the multi-dimensional effects of humans on water; and they will never do so until they are adapted to different geographical locations. Building a new model will likely entail creating smaller-scale versions that account for the geographically specific roles of humans in shaping water management and use. The cumulative sum of these smaller models may well provide a comprehensive model for water stewardship and use that advances integral human development for everyone on the planet.

Kellogg Faculty Fellow Ellis Adjei Adams is assistant professor of geography and environmental policy in the Keough School of Global Affairs.

Aidé Cuenca Narváez, Mohammad Farrae, Elischia Fludd, Donovan Leiva, and Alix Underwood are master of global affairs students in the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame. Joseph Gentine is a Notre Dame undergraduate majoring in environmental science and economics.

Photo: Mélissa Jeanty on Unsplash.