“The largest economic contraction since 1709’s great frost . . .”; “The largest collapse since the 1930s . . .”; “The largest recorded decline of output since 1947 . . . ”. In surveying the economic growth indicators for 2020 in thirty-two countries across the globe, the Keough School’s master of global affairs students were able to tell a simple, stark story: the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a massive economic collapse.

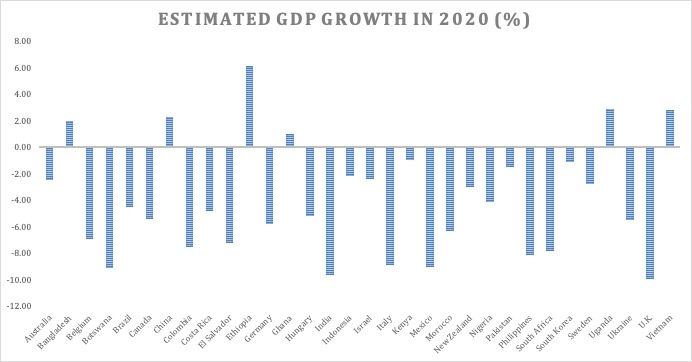

Indeed, international organizations seem to agree: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) characterized 2020 as “the Great Lockdown.” For the countries analyzed by the students, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) declined by an average of 3.9 percent in 2020. By comparison, the IMF estimates that global economic output declined by only 0.1 percent during the 2009 global financial crisis. Further, the extent of economic decline varied considerably across countries, as seen in the figure below.

What does the current global economic crisis entail for the integral human development (IHD) of humanity? Integral human development is primarily understood as a call for the development of every person and the whole person. As such, IHD emphasizes the importance of promoting the social, spiritual, and cultural dimensions of human development on an equal footing with the economic; the underlying assumption is that human dignity requires concurrent progress toward fulfilling each person’s potential on all of these fronts.

From this perspective, the current economic crisis presents a twofold challenge. First, as the student reports make clear through analyzing the qualitative cases that complement the data, the decline in GDP growth reflects sharp reductions in jobs, incomes, and livelihoods. Decline in these three markers risks undermining the possibility of providing for the basic needs of each person. Second, the unequal burdens of the crisis, both within and among countries, observed in the varying performances of different economies and sectors, risk leaving behind the most vulnerable nations and citizens. To deal with these challenges, governments have faced the conundrum that some policies that save lives and prevent the spread of the virus (such as strict lockdowns or mobility restrictions) may in fact result in serious economic slowdowns that could put these very lives at risk.

In this blog post, we argue that the unique lens of IHD provides an amplified horizon to understand the impacts of this pandemic and the policy responses deployed to address them.

Inequality exposed

Inequality has long been embedded in the global economy, affecting millions of people whose access to economic and social mobility is denied. The current health crisis and economic depression have further exposed and deepened this major challenge, with specific sectors, countries, and the most vulnerable carrying higher burdens than others.

In Bangladesh, global restrictions on travel had devastating effects on the country’s economy, with over 2.5 million jobs lost in the tourism sector alone. Similarly, the country’s garment sector, which accounts for 80 percent of the country’s exports, was forced to close 1,000 factories and lay off one million workers, in response to the reductions in global trade. This picture is reflected worldwide, with highly contact-intensive service sectors (such as hotels, restaurants, transportation, tourism etc) experiencing the greatest economic losses. Production of goods meant for export markets, as opposed to internal consumption, was also more severely affected.

As the Keough School’s Alejandro Estefan argues, exports of commodities such as oil and metals have been particularly affected, another trend that risks exacerbating global inequalities, given that these goods are exported mainly by developing countries. Such unequal economic performance among nations risks leaving behind people in the most vulnerable conditions. While some developing countries like Ethiopia, China, or Vietnam experienced only growth slowdowns rather than outright declines, other nations such as India and the Philippines exhibited drops in output of more than 8 percent.

The principle of leaving no one behind, which is the promise of the United Nations 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals, suggests that special attention may be required for specific economic sectors such as high-contact services and for the worst performing countries. The challenges of achieving global and sectoral equity are thus added to that of encouraging overall economic recovery.

Policy responses

To tackle the economic challenges triggered by the pandemic, the thirty-two examined countries came up with a wide range of fiscal and monetary policy measures. Most of these aimed to reduce the burdens suffered by businesses (from nascent to well established), while trying to boost the economy.

Many countries (including Bangladesh, Germany, Ethiopia, Israel, Australia, and the United Kingdom) chose to enact stimulus packages, either by giving money directly to citizens to boost consumption or by increasing government spending. Countries like Argentina and Brazil were able to offset a considerable amount of the lockdown-induced increase in poverty by greatly expanding their social assistance programs. Tax cuts (implemented in Hungary, Indonesia, Ethiopia, Kenya, El Salvador, and Ukraine, among others) were common measures that targeted either citizens (for example in the form of a tax relief on the individual’s salary) or companies or both. Tax cuts given to companies served as effective tools to motivate them not to lay off their employees. Some countries (e.g., Colombia, Hungary, Nigeria) implemented a credit repayment moratorium to provide relief to debtors. Many others (including Botswana, Hungary, and Belgium) decided to offer loans to the small and medium enterprises (SME) to enable them to keep operating.

Two specific examples showcase the effectiveness of fiscal policy responses. In Vietnam, a lower middle-income country, a US $10.8 billion credit support package, together with cash transfers for households and additional financial support for both employees and employers, helped keep consumption levels relatively stable. The country also contained the pandemic effectively via early lockdowns and border closures, which then allowed for a quick reopening. Germany, a high- income country, implemented three rounds of stimulus packages. The country’s Kurzarbeit program, which motivates employers to reduce their employees’ working hours instead of laying them off, has been notable in preserving employment. Since workers do not lose their jobs, they have less incentive to save on a precautionary basis and the program therefore acts as a stimulus to aggregate demand in the economy as well. Companies retain firm-specific human capital, while avoiding the costly process of separation, re-hiring, and training. Importantly, vulnerable citizens who were not covered by Kurzarbeit (e.g. marginal and self-employed workers) were given access to an expanded basic income program.

In terms of monetary policy, many countries lowered interest rates to historically low (or zero) levels. The central banks of Australia, Belgium, and New Zealand engaged in quantitative easing by purchasing longer-term securities from the open market in order to increase the money supply and encourage lending and investment. Central banks in several other countries (e.g., India, Indonesia, South Korea, El Salvador, the United Kingdom) reduced the required reserves that commercial banks need to maintain with the central bank. The central banks of Hungary, Belgium, India, and El Salvador introduced new measures to provide the SME sector with cheap loans.

Viewed through an IHD lens, the human-centered innovations that some of these policy responses exhibit are notable. Beyond the established macroeconomic levers such as tax cuts, cash transfers and monetary expansion, more unusual policies such as Kurzarbeit in Europe can be seen as beneficial for multiple dimensions of human well-being; they allowed for the maintenance of consumption but also honored the dignity that many beneficiaries associated with retaining stable employment.

Ongoing challenges

The biggest challenge in deploying fiscal policy measures is how to finance them. Some countries, like Germany, had adequate reserves and very low borrowing costs, which enabled them to fund generous programs. Others, like Mexico, decided to forgo massive expansion in social assistance programs due to concerns over financing and debt. International organizations can play a role in alleviating such financing constraints. Countries like Pakistan, South Africa, Colombia, Kenya, El Salvador, Ukraine, Uganda, and Costa Rica turned to the IMF for loans. In addition, the European Union announced the largest stimulus package ever financed through the EU budget.

Financing concerns can pose difficult social and political challenges. In Colombia, for instance, the government decided to fund its basic income program to support the country’s poorest families during the pandemic with expansions of the tax base. This resulted in widespread protests in an economic system already perceived as highly unequal; these protests have continued despite the withdrawal of the tax hike.

From an IHD perspective, the challenge of leaving no one behind requires that policymakers acknowledge these existing inequalities by asking questions such as: How is this policy prioritizing those most in need? How can we ensure that other sections of society will not be disadvantaged in the quest to help some people? And how should macroeconomic measures be structured to address psychological benefits in addition to material ones? While cases like Germany give reasons for hope, the situation in Colombia is a stark reminder of the importance of asking the right questions in policy design.

This blog post is based on macroeconomic reports compiled by the Master of Global Affairs Class of 2022, as part of the Economics of Growth and Development course. These reports have been summarized by Angelina Soriano Nuncio, Eduardo Pagés Jimenez, Imre Gabor Holtzer and Kellogg Faculty Fellow Lakshmi Iyer, associate professor of economics and global affairs. Original reports can be obtained by contacting Lakshmi Iyer.

Top Photo: Young Bangladeshi women being trained at the Savar Export Processing Zone training center in Dhaka, Bangladesh. © Dominic Chavez/World Bank.