This Q&A is part of an ongoing series with Arts and Letters graduate students. Read more Q&As with graduate students and faculty members here.

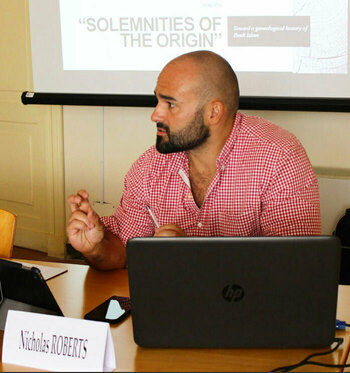

Nicholas Roberts completed his PhD in history at Notre Dame in May, focusing on modern Islamic history. He earned his Bachelor of Arts in music performance and history from Syracuse University in 2009 and his Master of Arts in global, international, and comparative history from Georgetown University in 2014. This fall, he is joining Norwich University as assistant professor of Middle Eastern history.

How did you choose Notre Dame?

How did you choose Notre Dame?

I’ve always loved history and that’s the initial cause – just a passion for the discipline of history and wanting to teach. I got a master’s degree in history at Georgetown University, which was really just confirmation that I loved being in graduate school, being a student, doing research, and writing. At our graduation at Georgetown, the speaker said that if you’re having trouble discerning what you should do, close your eyes and imagine somewhere you’re happiest – and for me, that was in the classroom. That’s what confirmed for me that I wanted to get my PhD. My former advisor at Georgetown was retiring, so I asked for his advice, and he said I should study with (Kellogg Faculty Fellow) Ebrahim Moosa, which is really what drew me to Notre Dame.

Tell us about your research interests. What are you working on right now?

My research basically tries to synthesize Islamic history or the history of the Muslim world with world history. Instead of showing how Europe is the center of the world with all these other peripheries, as many historians have, I try to show more that these different parts of the world – such as the Middle East, Africa, and the Indian Ocean – have actually been in the driver's seat of history for most of history. My dissertation was a history of the Omani Empire in the Indian Ocean, arguing that it was a formative space in the emergence of our modern-day world systems and global capitalism. I have a few other smaller projects that have spun off of that for journal articles, but the big project for the next maybe three years or so will be getting that published as a book.

What inspired you to do this research?

What inspired you to do this research?

As historians we look for gaps – we look for things that haven’t been written about and talked about, and so I don’t have a lightbulb moment where this came to me. It was kind of slowly over time looking at my field, looking at the terrain of historians who write about the Middle East and the Muslim world and just seeing that this was a whole area of history that had not been told. As I began doing the research, I discovered that it’s extraordinarily interesting history that’s also really dramatic. My dissertation uses the reign of one particular leader of the empire as a window for observing history. This leader came to power by murdering his uncle at the encouragement of his aunt, which is just one example of these crazy stories that I started to uncover. So that encouraged me to keep pursuing it.

How have the support and fellowships you’ve received from Notre Dame and your department enabled you to pursue your research interests?

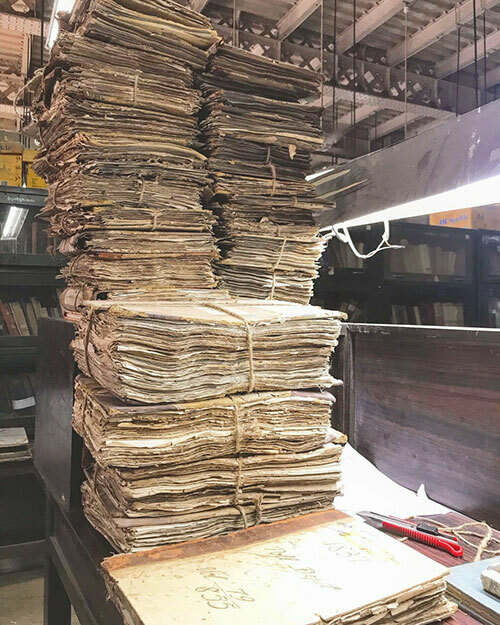

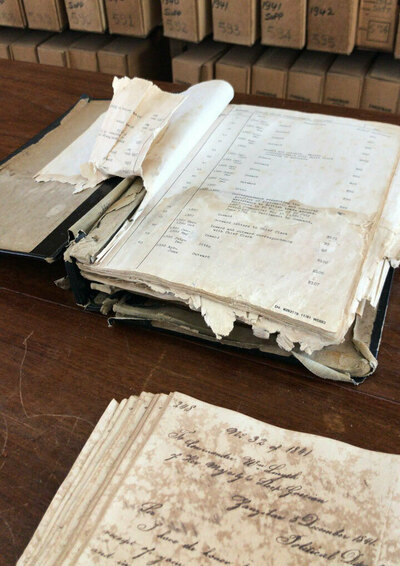

I used to tell people that I’m the luckiest PhD student in the US, and I mean that. I received the University Presidential Fellowship from Notre Dame, and this year I’m doing my fellowship through the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study. Additionally, the Department of History and my advisor in the Keough School for Global Affairs gave me a research and travel fund, and the dissertation would not have been possible without that. I was in about a dozen different archives or libraries throughout the world on four continents: Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America.

I was essentially following the old trade routes, and it really was so crucial to go to these places and archives in person to access sources. I traveled for 18 months, and it was by far the best 18 months of my life. I learned so much about the world, and it was just extraordinarily fun. If we taught history more like this, I think not so many people would say they disliked history in school. History is detective work. You come up with a question, and then you go out into the world to find the answer. A dissertation like the one I did is not really conventional with all of the travel and different languages and archives. The only way I got it done was with the support of my department and the support of Notre Dame.

You also received a Critical Language Scholarship. What role did language play in your research?

My dissertation uses Arabic and French, and I had to work through some Swahili while living in Tanzania and Zanzibar. When I arrived at Notre Dame, I needed to improve my Arabic training. The financial support of the graduate students here frees you from having to worry about missing out on an opportunity if you don’t get another source of funding. I was able to go live in the Middle East three separate times to focus on studying Arabic without having to worry about cobbling together all these sources of funding to live there because the fellowship was so generous. I also improved my French reading ability through my research. My first education of French was living in Tunisia in North Africa. I went there to study Arabic, but it’s a dual language country and I learned a lot there.

What makes the PhD in history program distinctive and why is it the best fit for you?

What makes the PhD in history program distinctive and why is it the best fit for you?

I think the biggest thing is that the department here has our best interests at heart, and I say that very genuinely because it’s not like that at a lot of graduate schools. The department at Notre Dame really works hard to give us everything we need to make sure we’re doing well. It’s nice knowing that our director of graduate studies has our back. It’s a friendly department too, and I’ve loved all of the faculty here. Additionally, when I first came to Notre Dame, I knew that Middle East history was not a very big program here. I knew I wouldn’t have all of these classes to take in my area, so I took a lot of American history classes because that’s what Notre Dame is known for.

Looking back, that was absolutely transformative in my education here. I wouldn’t replace that for the world because I think it’s important to step out of your own field and see things through the eyes of another person in a different field and then go back to your own work. It helps you think more creatively. The biggest impact on developing and completing my dissertation was a class I took here with assistant professor Emily Remus on the history of American capitalism. That was the main thrust of my dissertation — it made me think about how I can contribute to these debates by looking at a different part of the world.

Where are you headed after Notre Dame, and how do you feel the program has prepared you for the job market?

I’m headed to Norwich University in Vermont. I’ll be their professor of Middle East and African history, and I’ll also be leading their international studies program, which I’m really excited about. The first way Notre Dame has really prepared me might not be immediately evident. I came to Notre Dame to start as a research assistant for my advisor Professor Moosa before classes actually began in March before my fall semester. Even then, Notre Dame and Professor Moosa funded me to go to different conferences and one big summer school program in Turkey. That was five years ago, but even now, I still have these connections that I formed with people in these schools and language institutes overseas that I can now draw upon to start a summer Arabic program for my students at Norwich or things like that.

And then, of course, I’ve received a great education. I’ve been a student now for 25 years in total, and it was only here at Notre Dame that I had a professor edit my work with a red pen. I was shocked that he was actually reading my work and telling me to cut words or add a comma. It’s not that you would expect faculty to ignore your work, but especially at this level, you don’t expect them to be going through with a red pen. There’s really a close focus on the behalf of the faculty here on the students and that helped me in all sorts of ways.