When the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly halted international travel, Mary Shiraef’s fieldwork plan to investigate the outcomes of communist-era border policies in Albania was postponed indefinitely. So she pivoted.

When the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly halted international travel, Mary Shiraef’s fieldwork plan to investigate the outcomes of communist-era border policies in Albania was postponed indefinitely. So she pivoted.

The Kellogg doctoral student affiliate and Notre Dame political science doctoral candidate decided to map pandemic-induced border closures around the world. It wasn’t something she anticipated doing in graduate school, as she primarily works with historical data.

But when Shiraef realized the world’s new border closures were not being tracked, she saw a need.

“The World Health Organization didn't have a database of border closures,” she said. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention didn’t have a database.”

So in April 2020, Shiraef and two researchers from Stanford University’s Immigration Policy Lab analyzed a humanitarian organization’s data of border closures in a blog post.

“It was the most difficult blog post I’d ever written,” Shiraef said. “The facts just weren’t there.”

The team knew border closures were popping up every day that month, but where they were, when they were happening, and whether they would work was unclear. Drawing inference from the data was impossible because the data was being collected in crisis mode, not systematically.

Island countries weren’t included, and the sources for the policies were being wiped from the internet.

The high-quality sources that did exist were either targeted to the needs of specific travelers or were placed behind paywalls, making it impossible for the average citizen to see which border closures were in place when.

Shiraef then reached out to colleagues locally and globally to see if they wanted to help her investigate the effectiveness of international border closures.

“Twenty-five people responded in a week,” she said. “It was invigorating.”

An international effort

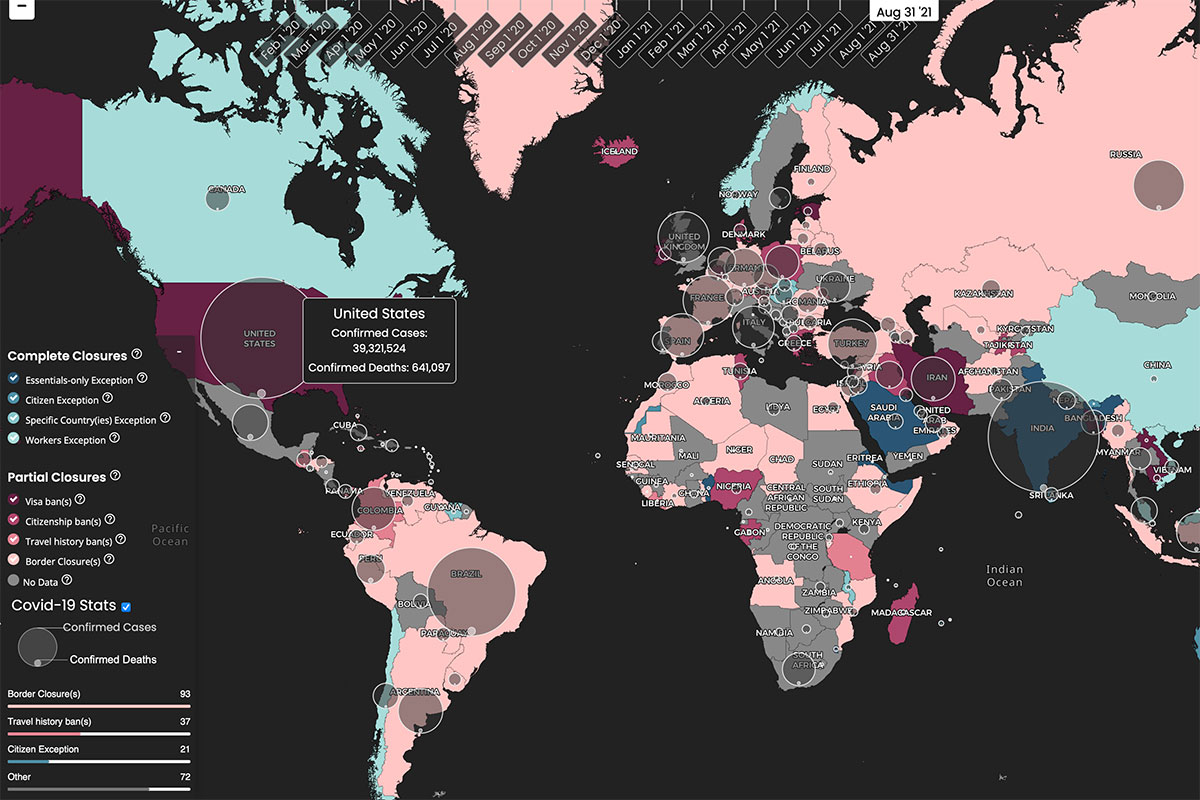

With support from volunteers from Notre Dame, Stanford, Emory, Brown, and Duke, as well as researchers in Germany and Japan, Shiraef decided to launch an online data collection effort – the COVID Border Accountability Project (COBAP). They quickly built the most comprehensive international COVID border closure database, including a user-friendly map visualization.

Kellogg PhD Fellow and Dissertation Year Fellow Paul Friesen, a political science PhD candidate, headed up the analysis, and an interdisciplinary team of three undergraduates in political science and one in biology helped source, categorize and hand-code more than 2,000 international border closures instituted in 2020–2021.

Kellogg PhD Fellow and Dissertation Year Fellow Paul Friesen, a political science PhD candidate, headed up the analysis, and an interdisciplinary team of three undergraduates in political science and one in biology helped source, categorize and hand-code more than 2,000 international border closures instituted in 2020–2021.

Those who speak second and third languages – including Arabic and French – recorded policies using their linguistic expertise. Undergraduates also corresponded with public officials to confirm dates and uncover policies missing from the database. Friesen analyzed complete and partial closures, as well as those that banned travelers from specific countries.

Two years later, the project has been reported on in more than 40 news outlets, the data was peer-reviewed and published in the Nature Portfolio’s Scientific Data, Scientific Reports published the open-source results, and the National Library of Medicine posted the study. The international research collaboration is still active and continues to provide valuable skills-development opportunities for Notre Dame undergraduates.

The team ultimately found no evidence that the international border closures reduced the spread of COVID-19 – including in island countries that completely closed.

“These results are surprising to many and less so to some,” Shiraef said. “My interpretation is that even when border closures appeared complete, there was almost always an exception or exemption, for essential reasons. And the timing of border closures is a critical factor – most were instituted in March 2020 or later, which we now have a stronger sense was after the novel coronavirus had already entered the countries undetected.”

The team did, however, find a strong association between domestic lockdowns and decreases in new cases of COVID-19.

Research informing policy

Friesen, the study’s second author, had rushed back to the United States in spring 2020 from Africa, where he had been conducting research on the nature of partisanship in Botswana and Zimbabwe. For COBAP, he wrote the code and conducted the analysis, implementing a cutting-edge matching technique to ensure the study compares similar countries to help reduce bias.

“I felt an urgency that these data needed to be analyzed,” he said. “It's a perfect example of where academia can and should inform policymakers – who, in this situation, seemed to be following conventional wisdom or a herd instinct on border closures. With any type of restrictive policy, people will suffer in different ways, and we need to know if that pain was worth it. I think our findings say that, in most cases, it wasn't, so hopefully we do it differently next time.”

For Shiraef, COBAP won’t end with the publication of the stud; she plans to stop when all the border closures introduced in response to the coronavirus pandemic are lifted. As of December 2021, more than 250 border closures remained, and many more were introduced in early 2022 in response to the omicron variant.

Friesen and Shiraef are now completing a third phase of the project exploring whether the border closures were science-based or driven by ideology. More than 10 undergraduates in political science are helping finalize the COBAP dataset.

“Looking back on COBAP’s work, I have learned on a personal and practical level how much science depends on the work of others. It takes time to grow knowledge, and there is still a lot we do not know,” Shiraef said. “We don’t know what factors motivated the variation in border closure types. For instance, many countries introduced bans that the media reported as biased against African countries, anti-immigration, or for other political reasons. That’s worth looking into.”

Valued contributors

The undergraduate students who got involved with COBAP as study research assistants – Kellogg Undergraduate Researcher Elizabeth “Lizzie” Stifel, Erin Tutaj, Nora Murphy and Hawraa Al Janabi – simultaneously gained meaningful research experience while making significant contributions to the project.

They checked countries’ websites to code their international lockdown policies, and contacted government officials in those countries to ensure accuracy. All are listed as co-authors on the study.

For Stifel, a sophomore political science and global affairs major with a data science minor, the project matched her interests and provided opportunities to learn new skills. The Easton, Pennsylvania, native speaks French and is interested in African politics, so her work primarily focused on French-speaking countries in Africa.

For Stifel, a sophomore political science and global affairs major with a data science minor, the project matched her interests and provided opportunities to learn new skills. The Easton, Pennsylvania, native speaks French and is interested in African politics, so her work primarily focused on French-speaking countries in Africa.

“I now have a sense of working with data, and will be applying this experience on my own independent research,” said Stifel, who is currently interning with the US Embassy in Dakar and hopes to pursue a career in international environmental policy or global health.

Erin Tutaj, a sophomore political science and global affairs major from Third Lake, Illinois, also appreciated the chance to contribute to, and learn from, the study.

“This project gave me an inside scoop into what graduate-level research looks like and the amount of detail, time, and organization needed for a successful outcome,” said Tutaj, who has a concentration in international peace studies and is a Notre Dame International Security Center fellow. “I enhanced my ability to process information and accurately label it within large amounts of reading/data.”

Senior political science major Nora Murphy said she improved her critical thinking skills, ability to communicate quickly and effectively, and ability to solve coding issues on a tight deadline.

Beyond the personal benefits, the Glynn Family Honors Program scholar and Phi Beta Kappa member said the study is an important public service project.

“I hope the results will be instructive for policymakers in the future when they have to make decisions that balance costs and benefits for policies like these,” she said. “I think it’s also important that the project and the database we compiled is completely open to public viewing so that anyone can view the results and data and draw their own conclusions.”