In the past, authoritarian regimes presented themselves as an alternative to democracy. Today they mimic democracy, allowing their constituents to believe they are a part of retaining or reviving democracy while silently undermining it. These regimes hold elections in which the opposition can participate, but adopt discriminatory procedures and use public resources to prevent any form of effective opposition. The erosion of democracy results in illiberal regimes, which use the law to progressively dismantle civil and political rights. The nature of these illiberal regimes makes it difficult to establish at what point they cross the boundary between their democratic origins and their authoritarian ambitions.

This phenomenon, common throughout the world, makes no ideological distinction. Think of Venezuela under Hugo Chávez and Nicaragua under Daniel Ortega, but also of Hungary under Viktor Orban, Poland under the Law and Justice Party, Turkey under Recep Erdoğan, the Philippines under Rodrigo Duterte, and India under Narendra Modi. Some colleagues in political science argue that we are witnessing a global wave of autocratization.

Purging and packing courts

Political attacks on the judiciary are defining moments in the processes of democratic erosion. When we look at cases of autocratization across the globe, the capture of constitutional courts is often the decisive moment in the slide towards authoritarian rule.

This should not be surprising. The idea of human dignity, writes our colleague Paolo Carozza, sustains “the very possibility of human rights as global principles that . . . help us condition sovereignty and hold accountable those who abuse power, especially the power of the state.” Those who abuse state power, however, work ardently to prevent such an interpretation of the law.

Illiberal regimes need to control the judiciary because it is only by doing so that they can consolidate an authoritarian electoral model. The mechanisms used to purge the high courts are diverse: a constitutional reform; an impeachment trial; legislation to expand the size of the constitutional court, curb its powers, or reduce the mandatory retirement age. Yet the underlying process is always similar: illiberal regimes use their legislative majorities to capture the judiciary and later use their control of constitutional interpretation to weaken electoral competition.

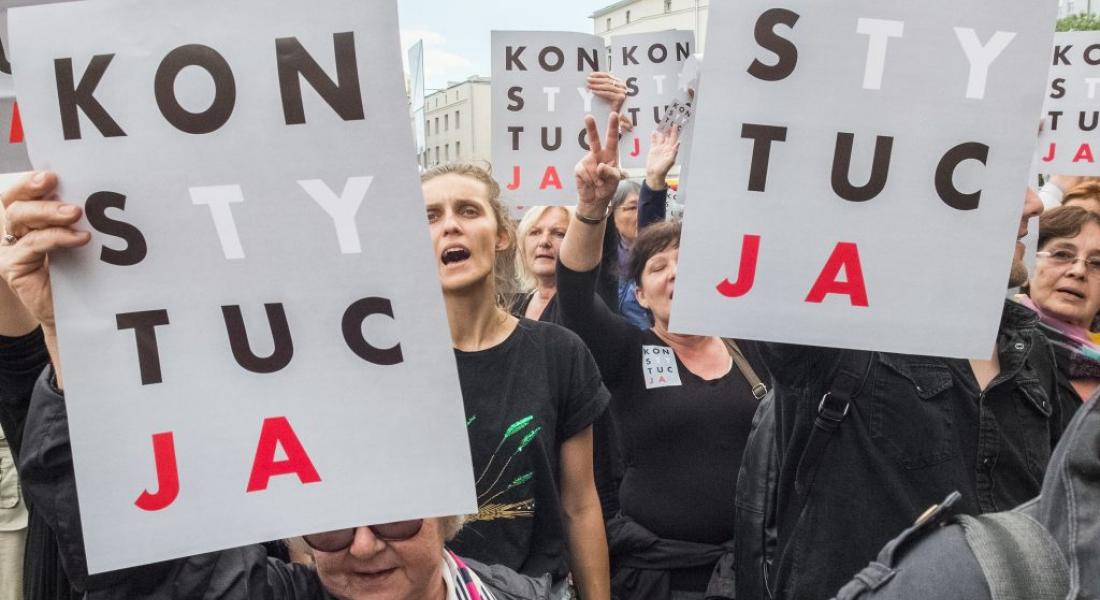

In Hungary, where the Fidesz party won a parliamentary supermajority in 2010, Parliament overturned all past jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court and used constitutional reforms to subdue the court. In Poland, the Law and Justice Party won a simple majority in the 2015 elections, and thus it took longer to capture the Constitutional Court. But by the end of 2017, it had control of the court and was able to advance on the ordinary judiciary.

Latin America has many examples of this problem, most recently in El Salvador. Last February, President Nayib Bukele’s party captured two-thirds of the seats in the legislative assembly. It took just two months for this majority to stage a purge. On May 1, the assembly dismissed the members of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court and the attorney general. President Bukele’s party is called Nuevas Ideas, but the idea of purging the high courts is not new in Latin America.

Cases of democratic erosion such as Hungary, Poland, El Salvador, Venezuela, and others suggest a key lesson: once the ruling party controls a supermajority in the legislature and the constitutional court, democracy is potentially at risk. This situation does not necessarily lead to the end of democracy, but it increases the risk of democratic breakdown significantly.

Collective protection

Voters can protect the independence of the judiciary by preserving a healthy partisan balance in the legislature, avoiding the creation of supermajorities. However, there are circumstances in which voters voluntarily surrender too much power to the governing party. This misstep often has irreversible consequences. History shows that politicians who receive a blank check always end up overdrawing from the account of popular will.

When partisan opposition is too weak to prevent an attack on independent courts, the last resort is, as recently noted by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the collective protection of human rights principles. Regional courts and the international legal community are important sources of resistance against domestic attacks on the judiciary.

In the Hungarian and Polish cases, the European Court of Justice played a central role, holding for example, that mechanisms to force judges into retirement violated principles of age discrimination in Hungary and principles of gender equality in Poland. The European Court of Human Rights also ruled against Hungary in the Baka case, stating that the purge of the president of the Supreme Court violated his right to freedom of expression. Similarly, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has defended judges against arbitrary dismissals in cases such as Constitutional Tribunal v. Peru, Reverón Trujillo v. Venezuela, López Lone et al. v. Honduras, or Colindres Schonenberg v. El Salvador.

From a “realist” perspective, it is easy to conclude that collective protection mechanisms are ineffective. In these cases, the European Union and the Organization of American States have been unable to reverse the processes of democratic erosion or restore the independence of the judiciary. However, international solidarity denies the ruling party the illusion of democratic legitimacy needed to justify its attacks on the judiciary. It challenges the official narrative and creates the conditions for redressing these violations through future reparations.

Collective protection mechanisms require strong international courts with a fluid dialogue with national judiciaries. The Court of Justice of the European Union claims authority to defend judicial independence because European national courts are dual institutions, applying national law as well as European law. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights, through the doctrine of conventionality control, assigns a similar role to national courts, which are responsible for applying the American Convention on Human Rights.

The construction of mechanisms of collective protection thus requires a new transnational consensus. In the age of democratic backsliding, legal education should also be “global citizenship” education, emphasizing the importance of international courts, promoting solidarity among judges worldwide, and facilitating strategic collaborations between judges’ associations and civil society.

Kellogg Faculty Fellow Aníbal Pérez-Liñán is professor of political science and global affairs in the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame. He studies processes of democratization, political instability, and the rule of law in new democracies.