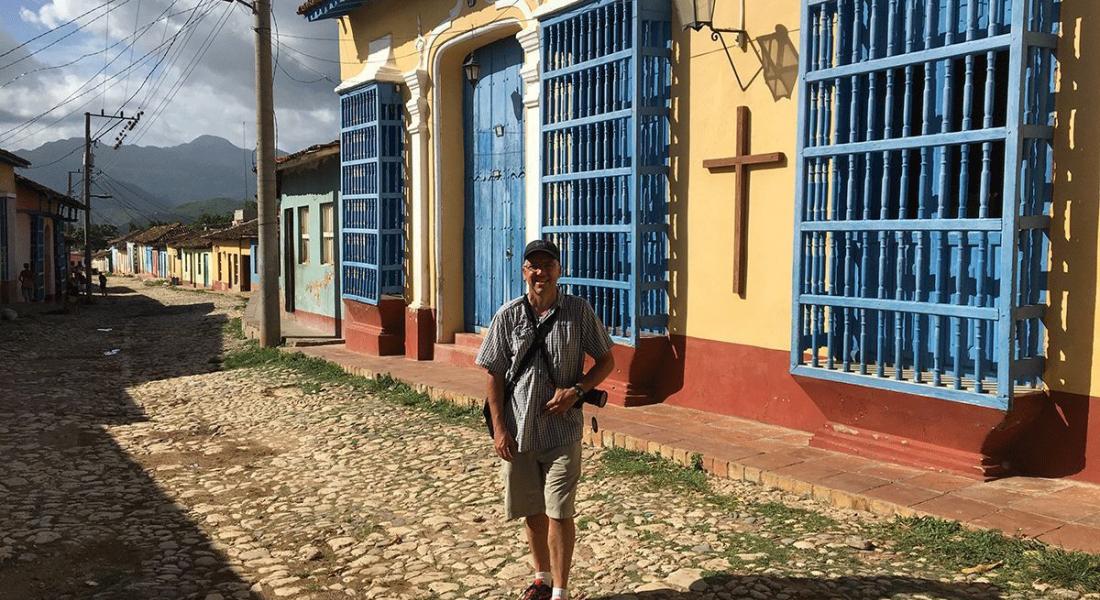

For Kellogg Faculty Fellow Thomas Anderson, it’s hard not to be fascinated with Cuba.

Anderson, a professor of Spanish and chair of the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, has written two books on Cuban literature and culture and has published an edited volume of a leading Cuban author’s letters. Currently, he is working on a book that focuses on images of the US civil rights movement in Cuban poetry.

“I think for a lot of people, Cuba has always been seen as this forbidden country, and it’s something people are drawn to,” he said. “But it’s also a country with an incredibly rich literary and cultural history.”

His work on Cuba is part of a larger focus on the Hispanic Caribbean—an area that is important to the United States politically, economically, and culturally, Anderson said.

His work on Cuba is part of a larger focus on the Hispanic Caribbean—an area that is important to the United States politically, economically, and culturally, Anderson said.

“I would consider myself a scholar of the Hispanic Caribbean—I also do work on Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and other countries in the area known as the Caribbean Basin,” he said. “And in the last six years, I’ve become especially interested in issues related to human rights across Latin America.”

That interest led to Anderson’s current book project, examining how Cuban poets responded to the US civil rights movement.

“It’s a complex topic because it isn’t just a study of the civil rights movement. Rather, it’s about how these authors—in a country that has always had a very contentious relationship with the United States—took what was happening in the US and turned it into a subject of literary texts that not only condemn many miscarriages of justice that took place during the civil rights movement but also racism in the United States in general.”

A more nuanced view

Anderson was inspired to write the book while teaching an undergraduate class on human rights in Latin American literature for the first time in 2011.

Throughout the semester, the class focused on texts dealing with civil and human rights issues in Latin American countries. But for a unit on Cuba, Anderson decided to focus not only on human rights violations in Cuba, but also on Cuban reactions to human rights violations in the United States.

The shift in perspective was an important aspect of the class, he said.

“Part of the problem with a class about Latin American human rights is that it can promote the stereotype that these violations are only happening there, or in other countries outside the US,” Anderson said, “and that the United States is a country where everything has always been fine.”

Anderson sees his research as valuable to both his students and a wider audience in North America and Latin America.

“On the one hand, I think that through reading and learning about the Cuban texts that I consider in my book my students can gain insight into the U.S. civil rights movement. Unless they take a class on African American history or U.S. history in the 1950s and ’60s, some of them might go through high school and college and never get a really in-depth view of it,” he said. “I also think it’s a way for them to see a nuanced view of Cuba. Because many of them come in with a skewed view of what Cuba is and what Cuban people believe.”

For Latin American audiences—and Cuban audiences, in particular—Anderson said the book is a reminder of an era many have forgotten.

One author he focuses closely on in the book project is Nicolás Guillén, an important member of a cultural and literary movement known as Afrocubanismo that flourished in the 1930s, and who, after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, was named the national poet of Cuba.

One author he focuses closely on in the book project is Nicolás Guillén, an important member of a cultural and literary movement known as Afrocubanismo that flourished in the 1930s, and who, after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, was named the national poet of Cuba.

“Nicolás Guillén was one of the very few poets of color who was really well known in Latin America. There are dozens of books and hundreds of articles on this poet and his work,” Anderson said. “But as I’m going through all of them, I’m finding that the many poems and essays that he dedicated to the civil rights movement are rarely even mentioned.”

Anderson said that given the current social and political climate in the US the time is right for the issue of civil rights in this country to be re-examined from another new perspective.

“Last year, I published a lengthy article—a version of one of the book chapters—in the leading Cuban peer-reviewed academic journal, Casa de las Americas,” he said. “And reactions have been very interesting. Several colleagues noted that they scarcely realized Guillén had written so passionately about cases like the murder of Emmett Till or the Little Rock Crisis of September 1957. A Cuban scholar mentioned to me that 10 years ago in Cuba, my article probably would not have been published given that human and civil rights — even when they pertain to another country — have long been sensitive topics in Cuba.”

A rich cultural history

Anderson’s first book, Everything in Its Place: The Life and Works of Virgilio Piñera, is a comprehensive study of one of Cuba’s leading 20th-century writers and thinkers. And his second, Carnival and National Identity in the Poetry of Afrocubanismo, explored representations of Afro-Cuban carnival celebrations in a variety of texts associated with the literary and cultural movement Afrocubanismo.

His most recent book, Piñera Corresponsal: Una Vida en Cartas, published last year, compiles letters Piñera wrote between 1958 and his death in 1979, during the first 20 years of the Cuban revolution.

“I think Piñera is an author I will always go back to,” Anderson said. “He is one of the most important playwrights in modern Latin America, and in Cuba, he’s very well known for his plays, short stories, novels, and poems.

A prolific writer, Piñera also had a daily literary column in the main newspaper of the revolution during its early years. In October 1961, however, he was arrested and ostracized for being gay.

“My first book on Piñera lays a very strong case that this important author might have been even more influential if he hadn’t been silenced in the last decade of his life,” Anderson said.

This fall, Anderson is teaching a survey course on Cuban literature from the mid-19th century to the present. The class, he said, is refreshing for students who only know about Cuba from a largely one-sided political context.

“Cuba is about so much more than just its relationship with the US, the fall of the Soviet Union, or the Cuban ‘special period’ in the 1990s,” he said. “And I think people in the United States need to know more about it. Key West is 90 miles from Havana, and yet it seems to so many to be so far away.

“It’s such an interesting, complex country to teach about and in which to conduct research. I am constantly learning new things and surprised at every turn. One of the reasons I love studying Cuba is that I feel like I could never learn everything there is to learn about it.”

First published at al.nd.edu