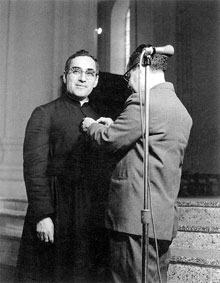

Archbishop Oscar Romero

Introduction

Introduction

Monsignor Oscar Romero y Galdamez, fourth archbishop of San Salvador, was assassinated while presiding at a memorial Mass in the Carmelite chapel of the Hospital de la Divina Providencia on March 24, 1980. The Archbishop was standing behind the altar, preparing the gifts of the offerty, when two mercenaries approached the chapel and fired a single shot from a U.S. military assault rifle. Archbishop Romero died within minutes from shock and blood loss. He died as a martyr and a prophet, as the greatest source of hope for millions of oppressed and impoverished Salvadorans, and as the greatest threat to the greed and arrogance of the oligarchy of 14 families that ruled El Salvador as if it were their own fiefdom.

Romero had undergone a Metanoia that transformed him from a timid defender of non- controversial virtues into a towering champion of the faith and of the faithful. He had discovered, in his own words: “The word of God is like the light of the sun. It illuminates beautiful things, but also things which we would rather not see.”

Much of the illuminated reality was utterly unconscionable. Less than a month after his installation as archbishop of El Salvador, his friend and colleague Rutillo Grande, SJ, was machine-gunned as “punishment” for helping peasants organize to secure self-determination. Soon after, a right-wing paramilitary group ordered all Jesuits to leave the country or to face execution. Although Fr. Grande’s murder had enormous impact on Romero, he realized that it was not an isolated incident. Literally tens of thousands of men, women, and children were murdered by military and para-military death squads under the guise of “anti-communism,” “law and order,” and “maintenance of traditional values.” On one day alone—January 22, 1979—paramilitary snipers killed 21 people and wounded 120 more while they were staging a peaceful protest march through downtown San Salvador. In rural areas, campesinos were murdered on a daily basis and their bodies were left to rot on road sides, as warnings to others who might “forget their place.” The death squads, commanded by Major Roberto D’ Aubuisson, a Salvadoran army officer who founded the right-wing ARENA political party, and self-proclaimed “fuhrer of San Salvador”— routinely murdered, tortured, raped, and looted with absolute impunity. The police and the courts existed primarily to exonerate the guilty and to punish those victims who dared to speak about the mistreatment they had suffered.

Beyond the overt violence, Oscar Romero saw institutionalized social and economic injustice on a pervasive scale. Two percent of the population controlled 57 percent of the nation’s usable land, and the 16 richest families owned the same amount of land utilized by 230,000 of the poorer families. The use of the comparative, rather than the superlative, is intentional since the poorest families had no land whatever, and were forced to sleep in ditches and muddy fields. Hungry farm workers were beaten or shot for eating a piece of the very produce they had grown. Mines and factories operated under the theory that it was cheaper to replace a dead or crippled worker than to repair defective equipment. Sixty percent of all babies died at birth, and 75 percent of the survivors suffered severe malnutrition. Hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children died from diseases that could have been cured by basic medications.

Facing such realities, Archbishop Romero began to ask his now-famous questions: “How can Christians do such things to each other? What can the Church do to help?” He found his answer in the realization that he had been called to Christ a second time, to the Christ who spoke to him in the Beatitudes. He found it also in the principles of the Liberation Theology that he had once condemned; in the voices that had risen at the Second General Conference of the Latin American Episcopate at Medellín, Colombia, and in the simple yet powerful truth of Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez’ dictum: “To know God is to do justice.”

In the last sermon Romero preached, only one day before his assassination, he spoke directly to the military: “I want to make a special appeal to soldiers, national guardsmen, and policemen: each of you is one of us. The peasants you kill are your own brothers and sisters. When you hear a man telling you to kill, remember God’s words, ‘thou shalt not kill.’ No soldier is obliged to obey a law contrary to the law of God. In the name of God, in the name of our tormented people, I beseech you, I implore you; in the name of God I command you to stop the repression.”

These are among the most famous of Monsignor Romero’s words, and they are the words that best define his Christianity, his ministry, and his character. In the 1988 Romero lecture, Archbishop Luciano Mendes, President of the Brazilian Conference of Catholic Bishops, told us: “[Archbishop Romero] was a man of nonviolence who paid a great price for his solidarity with the oppressed. His exhortation to the soldiers to lay down their arms and stop killing their own people was the last straw. Men of violence could not accept that a man of peace should ask people to stop killing.”

Monsignor Romero had long been aware that his vocation was a dangerous one. He saw himself denounced in the government-controlled media on an almost daily basis and he received numerous death threats. He responded by physically isolating himself from his colleagues and friends to the greatest extent possible, trying to prevent them from becoming collateral casualties, but he refused to be silenced. In his final Sunday homily, just one day before his assassination, he said: “I have no ambition of power and because of that I freely tell those in power what is good and what is bad, and I do the same with any political group—it is my duty.”

Just days earlier, Romero told an editor of the Mexican magazine Excelsior: “I need to say that as a Christian I do not believe in death without resurrection. If they kill me, I will rise again in the people of El Salvador…If they manage to carry out their threats, as of now, I offer my blood for the redemption and resurrection of El Salvador. If God accepts the sacrifice of my life, then may my blood be the seed of liberty and the sign that hope will soon become a reality. May my death, if it is accepted by God, be for the liberation of my people, as a witness of hope in what is to come. You can tell them that if they succeed in killing me, I pardon and bless those who do it. A bishop may die, but the Church of God, which is in the people, will never die.”

Archbishop Romero’s final prophecy is reiterated by Pope John Paul II in his 1994 apostolic letter, Tertio Adveniente: “At the end of the second millennium, the Church has once again become a Church of martyrs…It is a testimony that must not be forgotten.”

Similarly, in “Salvifici Doloris,” of 11 February 1984, on the Christian Meaning of Human Suffering, the Holy Father wrote: “This glory must be acknowledged not only in the martyrs for the faith but in many others also who, at times, even without belief in Christ, suffer and give their lives for the truth and for a just cause. In the sufferings of all of these people the great dignity of man is strikingly confirmed.”

These pages lead you through Romero's Life and the History of the Civil War in El Salvador. They contain information about past Lectures and their Speakers.

Remembering the testimony of Romero of the Americas and sharing his witness for faith, truth, and justice is the raison d’être of the annual Romero Days at the University of Notre Dame. Each year since 1987 we come together for seminars, workshops, memorial services, and major addresses that help us to honor Romero’s memory and to grow by virtue of what we learn of the extraordinary life and the tragic yet salvific death of the great martyr-prophet of the twentieth century, Oscar Arnulfo Romero.

Biography

Archbishop Oscar Romero (1917-1980)

Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Goldámez was born on August 15, 1917 in Ciudad Barrios, a Salvadoran mountain town near the Honduran border. He was the second of seven children of Guadalupe de Jesús Goldámez and Santos Romero, who worked as a telegrapher. Although better off financially than many of their neighbors, the Romeros had neither electricity nor running water in their small home, and the children slept on the floor.

Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Goldámez was born on August 15, 1917 in Ciudad Barrios, a Salvadoran mountain town near the Honduran border. He was the second of seven children of Guadalupe de Jesús Goldámez and Santos Romero, who worked as a telegrapher. Although better off financially than many of their neighbors, the Romeros had neither electricity nor running water in their small home, and the children slept on the floor.

Since his parents could not afford to continue Oscar’s education beyond the age of twelve, they apprenticed him to a local carpenter. Oscar immediately showed promise as a craftsman, but he was already determined to become an apprentice of the Carpenter of Nazareth. He entered the minor seminary in San Miguel at the age of thirteen, was promoted to the national seminary in San Salvador; and completed his studies at the Gregorian University in Rome, where he received a Licentiate in Theology. He was ordained in Rome in 1942. Unfortunately, his family could not attend his ordination because of WWII travel restrictions.

Although Fr. Romero hoped to pursue a doctorate in ascetical theology, he was called home to El Salvador in 1944 due to a severe shortage of priests. He initially served as pastor of a rural parish, but his exceptional skills and commitment marked him for greater responsibilities. He was soon appointed rector of the interdiocesan seminary and secretary of the Diocese of San Miguel, a position he held for 23 years. Recognizing the evangelical power of radio long before most of his contemporaries, he convinced five radio stations to broadcast his Sunday sermons to campesinos who believed they were unwelcome in the churches of their “betters.” Romero continued to rely on the electronic pulpit throughout the remainder of his life, making it a pillar of his ministries.

He also served as pastor of the cathedral parish of Santo Domingo, as chaplain of the Church of San Francisco, as Executive Secretary of the Episcopal Council for Central America and Panama, and as editor of the archdiocesan newspaper, Orientacion. The majority of his duties were administrative, a good match for the shy and introspective Romero who had serious doubts about his own “people skills.”

In 1970, he became Auxiliary Bishop for the Archdiocese of San Salvador, assisting the elderly Archbishop Luis Chávez y Gonzalez. Monsignor Chávez had been deeply influenced by the Second Vatican Council and was implementing progressive reforms in pastoral work throughout the Archdiocese. Many of these reforms—particularly lay leadership of catechists and delegates of the Word—troubled Romero who was then a doctrinal and social conservative and a staunch supporter of hierarchical authority. Indeed, Jesuit biographer describes the Romero of 1970 as: “Strong-willed and seemingly born to lead; yet he submitted unquestioningly to a structure that encourages conformity.” Romero diligently carried out the duties assigned to him by Archbishop Chávez but he was not comfortable with several of the programs. It was with some relief that he left the archdiocese in 1974 to become Bishop of Santiago de Maria, which includes his hometown, Ciudad Barrios.

In 1970, he became Auxiliary Bishop for the Archdiocese of San Salvador, assisting the elderly Archbishop Luis Chávez y Gonzalez. Monsignor Chávez had been deeply influenced by the Second Vatican Council and was implementing progressive reforms in pastoral work throughout the Archdiocese. Many of these reforms—particularly lay leadership of catechists and delegates of the Word—troubled Romero who was then a doctrinal and social conservative and a staunch supporter of hierarchical authority. Indeed, Jesuit biographer describes the Romero of 1970 as: “Strong-willed and seemingly born to lead; yet he submitted unquestioningly to a structure that encourages conformity.” Romero diligently carried out the duties assigned to him by Archbishop Chávez but he was not comfortable with several of the programs. It was with some relief that he left the archdiocese in 1974 to become Bishop of Santiago de Maria, which includes his hometown, Ciudad Barrios.

Bishop Romero’s hopes of escaping socio-political controversy were short lived. Popular resistance to economic and political oppression was growing as rapidly in Romero’s diocese as in any other part of El Salvador. Although a few farm workers and laborers saw armed revolution as the only viable recourse, the vast majority turned to the social teachings of the Church. Thousands joined Basic Ecclesial Communities (also known as Small Christian Communities) that sought to reform their society in the light of the Gospels.

The so-called “fourteen families” of the aristocracy termed all such activities “Marxist” and ordered the military to shoot strikers, union organizers, and human rights activists, especially teachers, nuns, and priests. The army’s efforts were supplemented by mercenary death-squads who roamed the countryside killing, raping, and torturing with impunity, and then collecting cash bounties on each man, woman, or child they victimized.

Romero strenuously denounced violence against people who had “…taken to the streets in orderly fashion to petition for justice and liberty,” just as he had denounced “…the mysticism of violence” being preached by the true revolutionaries.

His words were not heeded. On June 21, 1975, Salvadoran National Guardsmen hacked five campesinos to death in the tiny village of Tres Calles. Romero rushed to the site to console the families and to offer mass. Despite his lifelong determination to keep Church and politics completely separate, he denounced the attack as, “a grim violation of human rights.” That same day he wrote a letter of protest to Col. Arturo Armando Molina, head of the military dictatorship ruling the nation, and denounced the attack to the local National Guard commander personally. The commander pointed his finger at the bishop and replied: “cassocks are not bulletproof.” This was the first death threat directed at Romero, but it would be far from the last.

During his two years as Bishop of Santiago de Maria Romero crisscrossed his diocese on horseback, talking with laboring families to learn how he could best serve them. The reality of their lives horrified the bishop. Every day he discovered children dying because their parents could not pay for simple penicillin; people who were paid less than half of the legal minimum wage; people who had been savagely beaten for “insolence” after they asked for long overdue pay. Romero began using the resources of the diocese—and his own personal resources—to help the poor, but he knew that simple charity was not enough. He wrote in his diary:

During his two years as Bishop of Santiago de Maria Romero crisscrossed his diocese on horseback, talking with laboring families to learn how he could best serve them. The reality of their lives horrified the bishop. Every day he discovered children dying because their parents could not pay for simple penicillin; people who were paid less than half of the legal minimum wage; people who had been savagely beaten for “insolence” after they asked for long overdue pay. Romero began using the resources of the diocese—and his own personal resources—to help the poor, but he knew that simple charity was not enough. He wrote in his diary:

“The world of the poor teaches us that liberation will arrive only when the poor are not simply on the receiving end of handouts from government or from churches, but when they themselves are the masters and protagonists of their own struggle for liberation.”

Similarly, in a pastoral letter released in November 1976, he reflected on the plight of the thousands of coffee plantation workers in his diocese:

“The Church must cry out by command of God: ‘God has meant the earth and all it contains for the use of the whole human race. Created wealth should reach all in just form, under the aegis of justice and accompanied by charity…’ It saddens and concerns us to see the selfishness with which means and dispositions are found to nullify the just wage of the harvesters. How we would wish that the joy of this rain of rubies and all the harvests of the earth would not be darkened by the tragic sentence of the Bible: ‘Behold, the day wage of laborers that cut your fields defrauded by you is crying out, and the cries of the reapers have reached the ears of the Lord’ [James 5:4]”

Nevertheless, many regarded Romero as a conservative, both in his viewpoint and his practices, especially in comparison to the Archbishop Luis Chávez, who had reached mandatory retirement age. The government, the military, and the aristocracy were delighted to see the staunch defender of Godgiven human rights replaced by the “safely orthodox” Oscar Romero. Conversely, progressive pastoral leaders were hoping the Vatican would choose Bishop Arturo Rivera Damas instead of Romero, whom they remembered as a harsh critic of their liberation theology initiative. Clearly, both sides of the ideological spectrum had underestimated the scope of Romero’s now-famous “conversion.” As Oscar Romero was being installed as Archbishop of San Salvador, El Salvador was on the brink of civil war. The murder of campesinos was so common that it scarcely attracted attention from anyone except their families. General Carlos Humberto Romero (no relation) proclaimed himself President of El Salvador following a blatantly fraudulent election. Eight days later, scores of people were killed when the police opened fire on thousands of demonstrators protesting election corruption. That same month, three foreign priests were beaten and expelled from the country, and a Salvadoran priest was abducted, beaten nearly to death, and thrown through the doors of the chancery.

On March 12, 1977 a death squad ambushed Fr. Rutilio Grande, SJ along a road from Aguilares to El Paisnal, killing also the old man and young boy who were giving Fr. Grande a ride to the rural church where he planned to celebrate mass. Soon after, death squads killed another archdiocesan priest, Fr. Alfonso Navarro. Romero rushed to El Paisnal and offered mass in the house where Rutilio and the two campesinos had been carried. Romero was deeply saddened by the brutal murder of his friend and trusted aide, but he was also profoundly moved by the sugar-cane workers’ testimony to Fr. Grande’s works on their behalf and by their faith that Jesus would send them a new champion. Romero’s diaries clearly show that he believed he had been called once again.

On March 12, 1977 a death squad ambushed Fr. Rutilio Grande, SJ along a road from Aguilares to El Paisnal, killing also the old man and young boy who were giving Fr. Grande a ride to the rural church where he planned to celebrate mass. Soon after, death squads killed another archdiocesan priest, Fr. Alfonso Navarro. Romero rushed to El Paisnal and offered mass in the house where Rutilio and the two campesinos had been carried. Romero was deeply saddened by the brutal murder of his friend and trusted aide, but he was also profoundly moved by the sugar-cane workers’ testimony to Fr. Grande’s works on their behalf and by their faith that Jesus would send them a new champion. Romero’s diaries clearly show that he believed he had been called once again.

Two days later in a mass at San Salvador Cathedral, celebrated by 100 priests before an immense crowd in the plaza, Romero called Grande and his two companions “…co-workers in Christian liberation” and he declared,

“the government should not consider a priest who takes a stand for social justice as a politician, or a subversive element, when he is fulfilling his mission in the politics of the common good.”

Romero twice demanded that the President of El Salvador thoroughly investigate the murders. The government’s failure to offer more than lip-service condolences reinforced the archbishop’s growing conviction that the right-wing government was in collusion with the aristocrats who killed for personal gain. Realizing that his traditional reluctance to speak out on political matters had been a passive endorsement of repression and corruption. He notified the president that representatives of the archdiocese would no longer appear with government leaders at public ceremonies.

He also made the controversial decision to cancel masses throughout the entire country the following Sunday, except for the one on the steps of the cathedral, to which the faithful of all parishes were invited. More than 100,000 people attended. The event drew sharp criticism from the government, the military, and some factions within the Church, but it united the population and it clearly announced Romero’s belated acceptance of Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez’ dictum, “to know God is to do justice.”

A cornerstone of his efforts to “do justice” was his establishment of a permanent archdiocesan commission to find truth in a country governed by lies and to incontrovertibly document human rights abuses. When he visited the Vatican in 1979, Archbishop Romero presented the Pope with seven detailed reports of institutionalized murder, torture, and kidnapping throughout El Salvador.

He also wrote to President Jimmy Carter, appealing to him as a fellow Christian, to stop sending military aid to the Salvadoran government. His letter went unheeded. President Carter suspended aid in 1980, after the murders of four churchwomen, but President Reagan resumed and greatly increased aid to the Salvadoran government. In all, US aid averaged $1.5 million per day for twelve years.

Romero’s pleas for international intervention were ignored. To his dismay, so were his calls for solidarity with his fellow bishops, all but one of whom turned their backs on him. He continued to plead for an end to oppression, for reform of the nation’s deeply institutionalized structures of social and economic injustice, and for simple Christian decency. The rightists’ only response was an increase in the death threats against Romero and fire-bombings of the archdiocese’s newspaper and radio stations.

Four more priests were assassinated in 1979, along with many hundreds of catechists and delegates of the Word. The peasant death toll exceeded 3,000 per month.

In all, at least 75,000 - 80,000 Salvadorans would be slaughtered; 300,000 would disappear and never be seen again; a million would flee their homeland; and an additional million would become homeless fugitives, constantly fleeing the military and police. All of this occurred in a nation of only 5.5 million people.

Romero had nothing left to offer his people except faith and hope. He continued to use his nationally broadcast Sunday sermons to report on conditions throughout the nation, to reassert the Church’s prophetic and pastoral roles in the face of horrendous persecution, to promise his listeners that good would eventually come from evil and that they would not suffer and die in vain.

On March 23, 1980, after reporting the previous week’s deaths and disappearances, Romero began to speak directly to rank-and-file soldiers and policemen:

“Brothers, you are from the same people; you kill your fellow peasants…No soldier is obliged to obey an order that is contrary to the will of God…In the name of God, in the name of this suffering people, I ask you—I implore you—I command you in the name of God: stop the repression!”

The following evening, while performing a funeral mass in the Chapel of Divine Providence Hospital, Archbishop Oscar Romero was shot to death by a paid assassin.

Only moments before his death, he had reminded the mourners of the parable of wheat. His prophetic words:

“Those who surrender to the service of the poor through love of Christ will live like the grain of wheat that dies…The harvest comes because of the grain that dies…We know that every effort to improve society, above all when society is so full of injustice and sin, is an effort that God blesses, that God wants, that God demands of us.”

More than 50,000 people gathered in the square outside San Salvador Cathedral to pay their last respects to Archbishop Romero on March 30, 1980. As they waved palm fronds and sang, “You are the God of the Poor,” a series of small bombs were hurled into the crowd of mourners, apparently from the windows or balcony of the National Palace, which overlooks the Cathedral plaza, and cars on all four corners of the square exploded into flames. The blasts were followed by rapid volleys of gunfire that seemed to come from all four sides. Many witnesses saw army sharpshooters, dressed in civilian clothing, firing from the roof and balcony of the National Palace.

An estimated 7,000 people took sanctuary inside the cathedral, which normally holds no more than 3,000. Many others were crushed against the security fence and closed gates that were intended to provide security for the funeral mass.

Cardinal Ernesto Corripto Ahumado, representative of Pope John Paul II at the funeral, was delivering his tribute to Archbishop Romero when the first bomb exploded. The service was immediately postponed as clerics tried in vain to calm the panicked crowd. As gunfire continued outside the cathedral, Romero’s body was buried in a crypt below the sanctuary.

The attack left 40 mourners dead and hundreds seriously wounded. In an eyewitness account published in the March 31, 1980 Washington Post, Christopher Dickey wrote, prophetically:

“A highly popular and controversial figure and outspoken critic of the military that has long dominated this Central American nation, Romero was looked upon as one of the few people who could keep the violenceridden society from plunging into all-out civil war.”

Soon after Romero’s death, El Salvador was plunged into a full-blown civil war which lasted for twelve years. The United Nations Truth Commission called the war “genocidal”—a war that claimed more than 75,000 lives, if one accepts the Salvadoran government’s numbers, or more than three times that number if we accept the findings of most international investigating agencies.

Background

Although El Salvador declared independence from Spain in 1821, the legacy of colonialism continued throughout the twentieth century. Near-absolute power merely shifted from the Spaniards to the Salvadorans of European ancestry. Mestizos and indigenous peoples—some 95 percent of the total population were virtually serfs. A tiny aristocracy—known as “The 14 Families”—ruled the nation through a military commanded by mercenaries selected and paid by the richest landowners and industrialists. From 1933 - 1980, all but one president was a military dictator. Their regimes staged fraudulent elections periodically, to maintain the external pretense of democracy, but their regimes were based on repression blended with occasional reforms intended to defuse potential revolutions.

Although El Salvador declared independence from Spain in 1821, the legacy of colonialism continued throughout the twentieth century. Near-absolute power merely shifted from the Spaniards to the Salvadorans of European ancestry. Mestizos and indigenous peoples—some 95 percent of the total population were virtually serfs. A tiny aristocracy—known as “The 14 Families”—ruled the nation through a military commanded by mercenaries selected and paid by the richest landowners and industrialists. From 1933 - 1980, all but one president was a military dictator. Their regimes staged fraudulent elections periodically, to maintain the external pretense of democracy, but their regimes were based on repression blended with occasional reforms intended to defuse potential revolutions.

This system began to unravel in the 1970s, when previously splintered opponents of military rule united behind Jose Napoleon Duarte, leader of the Christian Democratic Party. Duarte and his broad-based reform platform were defeated in one of the most fraudulent elections in recorded history. Subsequent protests were crushed, and Duarte was exiled. These events convinced many—peasants and middle class alike—that reforms could not be achieved democratically when democracy itself was corrupt, and revolutionary groups grew rapidly. In 1980-83 there was

“unparalleled institutionalization of violence” in the words of the Commission on the Truth. “The main characteristics of this period were that violence became systemic and terror and distrust reigned among the civilian population. The fragmentation of any opposition or dissident movement by means of arbitrary arrests, murders, and selective and indiscriminate disappearances of leaders became common practice. Repression in the cities targeted political organizations, priests and nuns, students, trade unions, and organized sectors of Salvadoran society, as exemplified by the persecution of organizations such as the Asociación Nacional de Educadores Salvadoreños, murders of political leaders, and attacks on human rights bodies…Organized terrorism, in the form of the so-called “death squads”, became the most aberrant manifestations of the escalation of violence. Civilian and military groups engaged in a systematic murder campaign with total impunity, while state institutions turned a blind eye…This period saw the greatest number of deaths and human rights violations.”

1979 - 1984

1979

Oct. 15: The extreme right-wing government of Gen. Carlos Humberto Romero is overthrown by a coalition of moderate military officers and civilian leaders. The Revolutionary Government Junta (JRG), headed by Col. Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez and Col. Adolfo Majano, pledge to end repression and corruption; to protect human rights, and to distribute national wealth more equitably.

Nov: The JRG announces free elections will be held in 1982; it restricts landholdings to 100 hectares per owner; nationalizes banks, and recognizes all political parties. The ORDEN death squad is dissolved and the Salvadoran National Security Agency (ANSESAL) is dismantled.

1980

Jan 3: Facing death threats from the far right, all three civilian members of the Junta resign, as do 10 of the 11 cabinet ministers. The Revolutionary Government Junta is virtually paralyzed and unable to carry out many of its intended reforms.

Jan: Anti-government violence erupts—occupations of radio stations, bombings of government-controlled newspapers (La Prensa Gráfica and El Diario de Hoy), abductions, executions, and attacks on military targets. It is still not clear how many attacks were carried out by extremist groups such as the Fuerzas Populares de Liberacion (FPL) and the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP) and how many are the work of mercenaries controlled by neo-fascists who hope to create justification for extreme repression.

Jan: A wide array of left, center-left, and populist organizations including Bloque Popular Revolucionario (BPR), Ligas Populares 28 de Febrero (LP-28), Frente de Acción Popular Unificada (FAPU), and Unión Democratíca Nacionalista (UDN) unite, forming the Coordinadora Revolucionaria de Masas (CRM). They stage protest marches, sit-ins at government offices, and labor strikes to reinforce their demands for the release of political prisoners and medical care for the poor.

Jan 22: The National Guard attacks a massive CRM demonstration, described by Archbishop Romero as peaceful. They kill somewhere between 22 - 50 people and wound 600 - 800 others.

Feb. 6: US Ambassador Frank Devine informs the State Department. that mutilated bodies are appearing on roadsides just as they had during the worst days of Gen. Romero’s regime. He warns that the extreme right is arming itself and preparing for massive confrontations in which they clearly intend to ally with the military against both the government and the citizenry.

Feb. 22: Mario Zamora, Chief State Counsel and leader of the Christian Democrats, is murdered at his home, only days after Roberto D’Aubuissson—a former National Guard officer and death-squad commandant—accuses Zamora of being a communist agitator.

March 9: José Napoleón Duarte joins the Junta and leads the provisional government until the 1982 elections.

March 9: The Christian Democratic Party (PDC) expels Rubén Zamora, Dada Hizeri, and other progressive leaders. This seeming capitulation to rightists contributes to the political polarization that is spawning unprecedented increases both in death squad activities and in the numbers of previously apolitical peasants who join guerilla groups. US Congressional committee debates continuing military aid to El Salvador, decides to continue funding, despite Archbishop Romero’s plea for its termination.

March 24: Archbishop Oscar A. Romero is assassinated. The crime further polarizes Salvadoran society and presages the all-out war that will soon come. It also convinces many peasants that the Church cannot save them and that their only hope is armed revolution.

March 24: Archbishop Oscar A. Romero is assassinated. The crime further polarizes Salvadoran society and presages the all-out war that will soon come. It also convinces many peasants that the Church cannot save them and that their only hope is armed revolution.

March 30: During the archbishop’s funeral, bombs are hurled at the 50,000 - 60,000 mourners outside San Salvador Cathedral, and the panic-stricken mourners are strafed with gunfire. Forty-Two are killed and more than 200 are wounded.

May 7: Major Roberto D’Aubuisson is arrested with a group of military and mercenary followers. Weapons and documents seized during the raid implicate the group in planning and financing Archbishop Romero’s murder. The courts capitulate to waves of terrorist threats and institutional pressures from the far right and release D’Aubuisson. This strengthens the most conservative sectors of Salvadoran society and incontrovertibly reveals the passivity of the nation’s judiciary.

May 14-15: As many as 600 Salvadoran peasants are tortured and murdered by government forces near the Sumpul River.

Aug 12-15: A general strike called by FDR (a coalition of center-left parties) is violently suppressed, leaving 129 labor organizers dead.

Oct: The five largest revolutionary groups unite to form the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN). The Jesuit University of Central America is bombed twice, and Fr. Ignacio Ellacuria receives numerous death threats.

Nov: Ronald Reagan is elected President of the United States; he announces that he will greatly increase US aid to the Salvadoran military.

Nov. 27: Alvarez Córdoba and six FDR leaders are abducted, tortured, and murdered. Gen. Maximiliano Hernández Martínez of the Brigada Anticomunista issues a communiqué claiming “credit.”

Dec. 2: Four US churchwomen (Sr. Ita Ford, MM, Sr. Maura Clarke, MM, Sr. Dorothy Kazel, OSU, and laywoman Jean Donovan) are abducted, raped, and murdered by National Guard troops.

Dec 13: José!Napoleon Duarte becomes El Salvador’s first civilian president in 49 years.

1981

Jan 3: The President of the Salvadoran Institute for Agrarian Reform and two advisors are murdered in the Sheraton Hotel after they refuse to denounce land reform as a “Marxist conspiracy.” The murders are only one element of a systematic terror campaign directed at both the administrators and the beneficiaries of agrarian reform.

Jan 10: The FMLN launches coordinated guerilla attacks on military targets throughout the nation. Hundreds are killed on both sides.

Jan 14: The US government restores military aid, which had briefly been suspended due to public outrage stemming from the murders of the churchwomen. Washington praises the Salvadoran government for its resistance to “…a textbook case of armed aggression by communist powers. Much of this aid is used to create the Rapid Deployment Infantry Battalions (BIRI, Atlacatl, Atonal, Belloso,etc.)—the very groups that the Commission on Truth would later identify as “…the primary agents of war crimes.”

March 17: Salvadoran military stages land and air-based attacks on thousands of displaced peasants trying to flee across the Lempa River to Honduras. 20 - 30 people are killed and another 189 are never located. An additional 147 refugees, including 44 children, are slaughtered October 20-29 at the same river. In November, in Cabañas Department, government troops attack more than 1,000 people trying to escape to Honduras. Christian Legal Aid reports that displaced peasants, whose existence embarrasses the government, have become the targets of choice for both the military and the death squads.

Dec: Approximately 1,000 villagers are massacred by the Salvadoran Army in and around the village of El Mozote. Both the Salvadoran and US governments deny that the massacre occurred, but later admit their attempts to cover it up.

Dec: Christian Legal Aid reports 12,501 confirmed fatalities during 1981. The organization cannot even estimate how many thousands of deaths were not reported or could not be proven.

1982

President Reagan certifies that El Salvador is complying with human rights conditions for receiving US aid.

Jan. 31: Combined land-air military operations kill 152 civilians in Nueva Trinidad and Chalatenango.

Feb: FMLN attacks the Ilopango Air Force Base, destroying 6 of the Air Force’s 14 UH-1H helicopters, 5 Ouragan aircraft, and 3 C-47s.

Feb-April: FMLN carries out 439 acts of sabotage against economic targets, causing infrastructure damage totalling $98 million.

March 10: Some 5,000 peasants are fired upon by military helicopters as they fled from war-torn San Esteban Catarina.

March 10: The Alianza Anticommunists de El Salvador publishes a hit list of 34 people who are “discrediting the armed forces.” Most of the 34 are either journalists or clergy.

March 17: Four Dutch journalists are killed.

March 28: A new assembly is elected and the assembly chooses Alvaro Magana as president.

May: Military troops kill hundreds of civilians, burn houses, and destroy crops of peasant farmers in the province of Chalatenango.

May 24: The bodies of more than 150 men, women, and children are dumped at Puerta del Diablo, a clandestine site favored by the death squads.

May 27: The bodies of six members of the Christian Democratic Party are found at El Playón, another clandestine mass grave used by the death squads.

August: A military campaign of “pacification” in San Vicente kills 300 - 400 peasants.

Aug 31: CONADES reports there are 226,744 internally displaced persons wandering the roads of El Salvador and an additional 175,000 - 295,000 displaced persons living in exile in other countries. President Duarte strenuously denounces the rightists, holding them responsible for the murders of hundreds of Christian Democrats. Christian Legal Aid reports 3,059 political murders during the first eight months of 1982, saying, “nearly all of them the result of action by government agents against civilians not involved in military combat.” The Truth Commission estimates 5,962 civilians die at the hands at government forces. Once again, these are only the deaths that could be conclusively confirmed.

1983

President Reagan appeals to Congress for increased military aid to El Salvador.

Jan 15-18: FMLN guerillas temporarily occupy towns in Morazán. In a large-scale action, FMLN occupies Berlin, a city of 35,000, for three days, destroying the police and National Guard headquarters. The government responds with a large-scale counter-offensive. Monsignor Rivera y Damas reports that the rebels attack the military and the military attacks civilians.

Feb 22: Uniformed soldiers kidnapp, torture, and kill approximately 70 peasants from a cooperative at Las Hojas, Sonsonate.

March 16: Marianela García Villas, President of the Human Rights Commission of El Salvador a non-governmental organization is executed by security forces.

May 4: The Constituent Assembly passes an Amnesty Law for civilians involved in political offenses.

May 25: Col. Albert Schaufelberger is shot by rebels, becoming the first US military adviser to die in the war.

Aug 29-30: Negotiations begin between the government and the FDR- FMLN in San Jose, Costa Rica; no progress is made but both sides meet again in Bogotá on September 29.

Sept 25-26: The FMLN attacks army positions in Tenancingo; the military responds with aerial bombings that kill 100 civilians.

Oct. 7: Victor Manuel Quintanilla, senior FDR representative, is murdered along with three other persons. The Brigada Anticomunista claims responsibility.

Oct 7: President Magaña announces the next round of peace talks have been cancelled.

Nov 1: Gen. Maximiliano Hernández Martinez of the Brigada Anticomunista issues death threats to Bishops Rivera y Damas and Rosas Chavez, warning them to “…desist immediately from their disruptive sermons.”

Nov: Death squad activities increase sharply in October and November, as they had in May, in an effort to disrupt the continuing, albeit limited, dialogue between the government and the guerillas. Most of those murdered by death squads were leaders of the political opposition or were trade unionists, educators, journalists, or clergy.

Dec 9: Vice President George Bush visits San Salvador and warns that death squads must disappear because they threaten the viability of the government. He also demands the removal of certain military personnel and security officers who are guilty of human rights violations. There was a significant, albeit temporary decrease in activities of the squads.

Dec 15: A new constitution is approved, after 20 months of debate. It strengthens individual rights, establishes safeguards against excessive detention and unreasonable searches, a pluralistic republican form of government, strengthens the legislative branch, and enhances judicial autonomy. It also codifies the rights of laborers, especially agricultural workers. It is a very impressive document on paper, but there are no provisions to enforce it. FMLN begins using land mines on a large scale, causing many civilian deaths. Hostage taking and murders of mayors and government officials become frequent. The guerillas’ self-stated purpose is to demonstrate a “duality of power” in El Salvador. The government continues its policy of aerial bombing, artillery attack, and massive infantry campaigns against civilian populations in an effort to deprive guerillas of all means of survival causes increasing numbers of civilian casualties and displaced persons. The United Nations reports that 400,000 Salvadorans are displaced and homeless and an additional 700,000 are in exile abroad. Collectively, they represent 20 percent of the nation’s total population.

Dec 25: Monsignor Gregorio Rosas Chávez reports that 6,096 Salvadorans have been confirmed dead due to political violence. Approximately 4,700 were killed by the military and 1,300 were military or security forces. The year-end report of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights states: “…the number of civilians murdered for political reasons in El Salvador continues to be very high.”

1984

May 6: José Napoleón Duarte, a Christian Democrat defeats the neo- fascist Roberto d’Aubuisson in a runoff for the presidency. When Duarte takes office on June 1 he becomes the first civilian elected to the presidency in 50 years.

April: Legal Protection reports that death squad activities decreased markedly during the first months of the year, and increased significantly in April.

May 23: Five Salvadoran National Guardsmen are convicted of the murders of the US Churchwomen and are sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Sept: The UN Commission on Human Rights reports that political murders have declined significantly, but says: “…the persistence of civilian deaths in or as a result of combat weakens the favorable impression created by the decline in the number of political murders in non-combat situations.”

October: President Duarte invites the FMLN to talks at La Palma Chalatenango on October 15 and at Ayagualo, La Libertad, on November 30. The meetings fail to make substantial progress due to sharp differences about incorporation of FMLN into the political structure, but each side credits the other with negotiating in good faith.

1985 - 1992

1985

Negotiations between the government and the FMLN continue but produce no significant results.

March 31: Christian Democrats defeated rightist ARENA candidates in a majority of the Legislative Assembly races and municipal elections.

June 19: A Partido Revolucionario de Trabajadores Centroamericanos (PRTC) attack on a restaurant in San Salvador kills 4 US Marines and nine Salvadoran civilians.

Sept: After the army captures PRTC Commander, Nidia Diaz, the FMLN abducts President Duarte’s daughter, Inés Guadalupe Duarte. Fr. Ellacuria and Archbishop Rivera Damas negotiate a settlement that exchanges Ms Duarte and 22 mayors for Nidia Díaz and 21 other rebel leaders. Fascist death squad activity continues, but seems to be directed at government and rebel leaders almost equally. Legal Protection documents 136 murders by death squads in 1985. FMLN continues to use land mines. Legal Protection reports 31 deaths; the Human Rights Commission of El Salvador (governmental) reports 46 killed and 100 injured by mines in 1985. For the first time in the 1980s, the military does not commit any large- scale massacres. However, intensive aerial bombings kill and displace many innocent bystanders. Christian Legal Aid attributes 1,655 civilian non-combatant deaths to government forces.

1986

Jan: The Salvadoran military begins “Operation Phoenix” in an effort to regain the Guazapa area from FMLN control. The year-long military operation fails to drive out the guerilla forces, but it displaces huge numbers of rural people driving them from their homes. Displaced people form the Coordinadora Nacional de la Repoblación (CNR) that seeks to establish the right of civilians to live in the areas from which they came. The resettlement movement is supported by the Church. Political dialogue between the government and the FMLN remains deadlocked despite repeated efforts by the international community and the Church. President Duarte proposes peace plans on three occasions, but the FMLN rejects key provisions in each. Violence continues to decrease, relative to earlier years, but Operation Phoenix and repressive measures of state security forces produce casualties, as do abductions, summary executions, attacks on mayor’s offices, and mines laid by the FMLN. The civil war continues to depress both agricultural and industrial production, and the process of economic recovery is slow. Duarte adopts programs of economic stabilization and rejuvenation, but the economic crisis deepens and begins to threaten Duarte’s presidency. As the power increases in the rightist ARENA Party, it tries to strip Fr. Ellacuria of his citizenship and drive him from the country.

1987

Labor, student, and campesino groups organize numerous demonstrations demanding negotiations to settle the civil war. However, dialogue between the parties remained at a standstill and, in the words of the UN Truth Commission “…it became clear that human rights violations were being fostered by institutional shortcomings, complicity, or negligence, and they were the main obstacles to the peace process.” Progress is made in what the international community termed “the humanization of the conflict, but there was a resurgence of violence against the labor movement, human rights groups, social organizations, and religious organizations. At the same time, the FMLN continued its campaign of abductions and murders of civilians affiliated with the government or the armed forces.

August: Five Central American presidents meet in Guatemala and sign the Esquipulas II Agreement, calling for establishment of national reconciliation commissions in each country, an International Verification Commission, and amnesty legislation. The Papal Nuncio offers to host meetings between the government and the FMLN-FDR, Archbishop Rivera y Damas serve as moderators. The government and the FMLN-FDR endorse the Esquipulas II Agreement and announce establishing commissions to negotiate a cease-fire and other crucial points. The Legislative Assembly passes an “Amnesty Act Aimed at Achieving National Reconciliation.” The United Nations Commission on Human Rights Special Representative for El Salvador and human rights groups such as Americas Watch sharply criticize the scope of the amnesty, which extends to even the worst war criminals. Christian Legal Aid files lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of the article that extends amnesty to every offense. Herbert Anaya Sanabria, coordinator of the Human Rights Commission (non-governmental) is murdered by a death squad. The incident causes enormous outrage. The United Nations Special Representative, José Antonio Pastor Ridruejo reports more humanitarian conduct by the armed forces than in any previous year. There have been no reports of mass murders or torture by the Salvadoran Armed Forces. He concludes that, for the first time, the guerillas are responsible for the majority of civilian deaths, primarily because of land mines. He also cites forcible recruitment of minors by guerilla forces. Overall, however, there is a significant decline in civilian casualties compared to 1986. Gen. Adolfo Blandón, Chief of the Armed Forces Joint Staff, reports at year’s end that 470 military personnel had been killed and 2,815 wounded; rebel casualties totaled 1,004 dead, 670 wounded, and 847 taken prisoner.

1988

ARENA wins a majority in the elections for the National Assembly, after FMLN urges its supporters to boycott the election. Although the economic crisis was probably the major reason for the Christian Democrat’s loss, ARENA politicians claim the voters have mandated a return to far-right policies. The army resumes mass executions in San Sebastián and elsewhere. Death squads become more active again, killing an average of eight people per month—three times higher than in 1987. The Supreme Court exonerates the perpetrators of the Las Hojas Massacre, as well as those accused of the murders of the Director of ISTA and his American advisers. FMLN rebels kill eight mayors and threaten the lives of a similar number of suspected military informers.

1989

The Truth Commission’s reports “Two contradictory trends characterized Salvadoran society in 1989. On the one hand, acts of violence became more common, as did complaints of human rights violations, while on the other, talks between representatives of the Government of El Salvador and members of the FMLN leadership went forward with a view to achieving a negotiated and political settlement of the conflict.” Alfredo Cristiani, a right-wing extremist, is elected president.

April: Attorney General Roberto Garcia Alvarado is assassinated. Salvadoran military officers claim the assassination was plotted by the Jesuits at Central American University.

June: Jose Antonio Rodriguez Porth, the President’s Chief of Staff, is assassinated. The government begins systematic intimidation and harassment of pastoral workers and social workers churches and religious organizations.

Sept-Oct: the government and the FMLN continue peace talks in Mexico City, San Jose, Costa Rica, and in Caracas, Venezuela. President Cristiani asks Fr. Ellacuria to join a committee investigating a National Trade Union Federation bombing that killed 10 and wounded 35.

Nov. 13: The Jesuit residences at the University of Central America are ransacked by the army’s Atlactl battalion.

Nov. 15: Senior Salvadoran military officers give orders to kill Fr. Ellacuria and all witnesses.

Nov. 16: Army troops drag six Jesuit priests (Ignacio Ellacuria, Rector of the University of Central America; Segundo Montes, Ignacio Martin-Baró, Armando López, Juan Ramón Moreno, and Joaquín López), their housekeeper, Elba Ramos, and the housekeeper’s daughter, Celina Ramos from their beds and shoot them to death at the Jesuit residence of the UCA.

Nov: US government evacuates all nonessential diplomatic personnel.

Government security forces bomb FENESTRAS headquarters.

Nov 11: The FMLN retaliates for the bombing with the largest offensive of the war, attacking military centers in major cities throughout the nation. Fighting continues until December 12, claiming 2,000 lives on both sides and causing approximately 6 billion colones in property damage. The government responds to the FMLN with indiscriminate aerial bombardment of urban areas, and tortures and murders noncombatant civilians. These tactics swing public opinion sharply towards the FMLN.

1990

Feb 23: Former President José Napoleón Duarte dies. The FMLN proclaims a unilateral cease-fire on February 24 and 25.

Feb: US Congressman Joe Moakley, (D., MA), and his Special Task Force on El Salvador conduct an on-site investigation of the murders at the University of Central America. His report accuses the Armed Forces of impeding the investigation. The US House of Representatives cuts aid to El Salvador by 50 percent. The ferocious battles of November and December 1989 convince both sides that a decisive military victory is nearly impossible, and agree to resume negotiations to end the civil war through political means. Following a request from the Central American presidents, the UN begins to mediate talks between the two sides and intervens at crucial moments to keep the parties from leaving the negotiating table.

April: the government and the FMLN sign the Geneva Agreement, irreversibly committing themselves to an agenda and timetable for peace.

May 21: Both sides agree to the Caracas Agenda to end the conflict.

July 26: The San Jose Agreement on Human Rights is signed, and two final meetings are scheduled for 1991.

August: Peace talks regarding the military deadlock, leads the Secretary General of the UN to demand that future talks be conducted on secret to avoid political grandstanding. Col. Ponce is named El Salvador’s Minister of Defense despite accusations of his involvement in the murder of the Jesuits.

November: FMLN steps up its military operation to move stalled negotiations. The international community appeals to the FMLN to desist, and it does.

Dec: A US Army major implicates Col. Benavides of the Salvadoran Army in the murders at the University of Central America. Benevides is arrested.

Dec: The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reports that 53 people were executed by death squads and 42 by the Army. FMLN executed 21 persons, of whom 14 were considered political murders. Nevertheless, there were fewer civilian deaths in 1990 than in 1989. The numbers dropped sharply after the San Jose Agreement on Human Rights was signed. The army’s operations killed 852 persons, but it is not known how many were FMLN combatants or how many were civilians.

Dec: The Special Representative of the UN expresses the concerns of the Commission on Human Rights about the “alarming frequency” of murders, rapes, robberies, and abuse of authority committed by members of civil defense units, keeping the public in a constant state of fear.

1991

Jan. 2: FMLN forces shoot down a helicopter manned by three American military advisors near San Miguel and execute the two survivors.

Jan. 3-6: Negotiations in Mexico yield no concrete results.

Jan. 21: Army troops execute all 15 members of a family in El Zapote.

March: FMLN announces it will no longer boycott elections.

April 4-27: Government and FMLN negotiators meet in Mexico City for their 8th round of discussions. They agree to establish the Commission on the Truth, and reach significant agreements regarding constitutional reform of the armed forces, the judiciary, and the electoral system. Congressman Moakley announces that the Jesuits’ murder was planned at a secret meeting of senior Salvadoran military officers including Gen. Bustillo and Cols. Ponce, Zepeda, and Fuentes. Col. Benavides and Lt. Mendoza are convicted of the murders at the University of Central America.

July 26: The United Nations Observer Mission in El Salvador is launched and its Human Rights Division becomes operational.

Sept. 25: At the invitation of the Secretary-General of the UN, representatives of the Salvadoran government and the FMLN meet in New York City to sign an accord that establishes the National Commission for the Consolidation of Peace composed of representatives of the government, the FMLN, and other political parties, with observers from the Catholic Church and the UN. The New York City Accord also defines procedures for reforming and downsizing the army.

Dec. 31: The government and the FMLN initialed a peace agreement under the auspices of UN Secretary-General Perez de Cuellar.

1992

Jan.16: The final peace treaty—the Accords of Chapultepec—are signed in Mexico City, ending 12 years of tragic war that nearly destroyed El Salvador.

Feb. 1: A 9-month ceasefire takes effect and is not broken.

Aug: Jose Maria Tojiera, the Provincial of Central America, petitions the Salvadoran National Assembly to pardon Col. Benavides and Lt. Mendoza for the murder of the Jesuits.

Nov: the U.N. Truth Commission begins investigating acts of violence committed during El Salvador’s civil war, and subsequently publishes its reports.

A ceremony marks the official end of the conflict, concurrent with the demobilization of the FMLN military structure and the FMLN’s inception as a political party.

Subsequent Development

March 20, 1993: Blanket amnesty is granted to all accused of atrocities during the civil war.

March, 1994: El Salvador holds its first national elections that include candidates of the FMLN and other opposition parties. The United Nations oversee the election process. The Arena Party wins the presidency after a run-off and wins a majority in the National Assembly. The FMLN emerges as a major political force.

March, 1996: The FMLN wins 45 percent of National Assembly seats and mayorships of many key cities, including San Salvador.

1999-2000: William Ford, brother of one of the churchwomen murdered in El Salvador in 1980, files a civil suit against Gens. Garcia and Casanova, who have been implicated in their murders, after both are granted permanent residence in the US. The jury finds both defendants “not necessarily responsible.”

2000: The Salvadoran Attorney General begins investigations of former President Cristiani, Gen. Ponce, and Gen. Bustillo in the murders of the Jesuits at UCA.

Films and Videos

MONSEÑOR (Monseñor, the Last Journey of Oscar Romero) (March 2010)

Romero: Heartbeat of El Salvador - DVD: Original RISE Theatre Cast Recording (available for purchase or watch trailer)

Romero, starring Raul Julia and Richard Jourdan, 1989, 105 minutes (available in the OIT Media Resource Center of the University of Notre Dame)

Roses in December, a film by Ana Carrigan & Bernard Stone, 1982

School of Assassins, narrated by Susan Sarandon, 1995, 18 minutes; Academy Award nominee for Best Documentary

Enemies of War, a film by Esther Cassidy, PBS, 1999, 57 minutes

Killing Priests Is Good News, BBC, 1990, 57 minutes

A Question of Conscience, Icarus/Tamouz Productions, 1990, 43 minutes

Books - Additional Readings

Archbishop Oscar Romero: A Shepherd's Diary.

Translated by Irene B. Hodgson; fwd. by Thomas E. Quigley. London: CAFOD, 1993.

The Violence of Love: The Pastoral Wisdom of Archbishop Oscar Romero.

Compiled and translated by James R. Brockman, S.J.; fwd. by Henri J. M. Nouwen (San Francisco & Toronto: Harper & Row, 1988; reprinted Farmington, PA: Plough Pub., 1998)

The Church Is All of You: Thoughts of Archbishop Oscar A. Romero.

Compiled and translated by James R. Brockman, S.J. (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1984)

Voice of the Voiceless (The Four Pastoral Letters and Other Statements).

Ed. by R. Cardenal, I. Martin-Baró, and J. Sobrino; trans. by Michael J. Walsh (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1985)

Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero: Prophet to the Americas.

Margaret Swedish, (Washington, DC: Religious Task Force on Central America, 1995)

Romero, a Life.

James R. Brockman, (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1989)

Archbishop Romero: Memories and Reflections.

Jon Sobrino, (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1990)

Oscar Romero: Reflections on His Life and Writings.

Marie Dennis, Renny Golden, Scott Wright. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2000

La voz de los sin voz: La palabra viva de Monseñor Romero.

Ed. by Jon Sobrino, Ignacio Martin-Baró, and Rodolfo Cardenal (San Salvador: UCA Editiores, 1980)

From Power to Communion: Toward a New Way of Being Church Based on the Latin American Experience.

Ed. by Robert S. Pelton, C.S.C. (Notre Dame & London: University of Notre Dame Press, 1994)

Martyrs: Contemporary Writers on Modern Lives of Faith.

Ed. by Susan Bergman (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1998)

Freedom Made Flesh: The Mission of Christ and His Church.

Ignacio Ellucuria, trans. by John Drury (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1976)

Jesus Christ the Liberator: A Historical-Theological Reading of Jesus of Nazareth.

Jon Sobrino (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1993)

Revolution in El Salvador: Origins and Evolution.

Tommie Sue Montgomery (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1982)

The Principle of Mercy: Taking the Crucified People from the Cross.

Jon Sobrino (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1994)

Martyrdom and the Politics of Religion: Progressive Catholicism in El Salvador’s Civil War.

Anna L. Peterson (Binghampton, NY: SUNY Press, 1997)

The Religious Roots of Rebellion: Christians in Central American Revolutions.

Phillip Berryman (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1984)

Stubborn Hope: Religion, Politics and Revolution in Central America.

Phillip Berryman (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1995)

Gospel and Mission: Spirituality and the Poor.

Juan Ramón Moreno (Manilla: Cardinal Bea Institute, Ateneo de Manilla University, 1995)

A Retreat With Oscar Romero and Dorothy Day: Walking With the Poor.

Marie Dennis (Cincinatti: St. Anthony Messenger Press, 1997)

Companions of Jesus: The Jesuit Martyrs of El Salvador.

Jon Sobrino and Ignacio Ellucuria. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1990)

The Harvest of Justice: The Church of El Salvador Ten Years After Romero.

Daniel Santiago (NY: Paulist Press, 1993)

The Protection Racket State: Elite Politics, Military Extortion, and Civil War in El Salvador.

William Stanley (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996)

Cry of the People: United States Involvement in the Rise of Fascism, Torture, and Murder and the Persecution of the Catholic Church in Latin America.

Penny Lernoux (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980)

Fascism’s Return: Scandal, Revision, and Ideology Since 1980.

Ed. by Richard J. Golson (Lincoln, NE and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1998)

War Against the Poor: Low Intensity Conflict and Christian Faith.

Jack Nelson-Pallmeyer (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1989)

Faith of a People: The Life of a Basic Christian Community in El Salvador, 1970-1980.

Pablo Galdámez (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1986)

Death and Life in Morazán: A Priest’s Testimony from a War Zone in El Salvador.

Maria López Vigil (Washington: EPICA, 1989)

Related Links

RISE Theatre's play Romero: Heartbeat of El Salvador, DVD filmed with a live audience

Notre Dame Grad Releases New Rock Song about Archbishop Romero

The Archbishop Romero Trust

This website makes available a precious resource bank of materials on Archbishop Romero’s life and martyrdom.

Monseñor Romero

Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes

http://cervantesvirtual.com/bib_autor/romero/index.html

“The Reluctant Conversion of Oscar Romero”-Sojourners Net

https://sojo.net/magazine/march-april-2000/reluctant-conversion-oscar-romero

“Father Romero and the Treadmill of Heroism”

The Washington Post, March 28, 1980

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1980/03/28/father-romero-and-the-treadmill-of-heroism/fb522bb7-b8fd-4127-9c10-d971f731e8de/

“Martyrdom and Mercy”

Leo J. O’Donovan, S.J., President, Georgetown University

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1989/11/19/martyrdom-and-mercy/24fb606d-b4c0-4e2e-b444-edbc9b0e9e0d/

Select Bibliography and Visual Resources: The UCA Martyrs, Archbishop Romero, The Four Churchwomen, and the Church of the Poor in Central America

https://onlineministries.creighton.edu/CollaborativeMinistry/Martyrs/Romero/index.html

Romero, Oscar A-BBCi News

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8580840.stm

Romero, Oscar A-Resources for Catholic Educators

http://www.4catholiceducators.com/romero.htm

Archbishop Oscar Romero: A Disciple Who Revealed the Glory of God by Damian Zynda. Chicago: University of Scranton Press, 2010

https://www.amazon.com/Archbishop-Oscar-Romero-Disciple-University/dp/1589662113/ref=sr_1_5?ie=UTF8