Figure 1: Experimental Solar Panels on the Roof of Hassan II University of Casablanca’s Faculty of Science and Technology in Mohammedia. Source: Author.

From August to October 2024, Kellogg PhD Fellow William Kakenmaster (political science) traveled to Morocco on a Kellogg Institute Graduate Research Grant to conduct research for his project “Decarbonizing the Desert: Explaining Renewable Energy Trends in the Middle East and North Africa.” Upon his return, he sent the following summary of his work.

Morocco is going all in on clean energy, not just as a way to deal with climate change but to grow the economy and secure the country’s energy independence as well.

In 2009, the Kingdom passed major reforms designed to dramatically increase its renewable electricity capacity. The country set ambitious targets for wind and solar energy production and overhauled its energy agencies to encourage new investment into emerging renewable energy industries. At the Paris Climate Summit in 2015, Morocco doubled down on its ambitions and announced a goal of reaching 52% installed renewable capacity by 2030. These aspirations aren’t necessarily surprising, as plenty of countries have begun to embark on a transition to clean energy. What’s more incredible, so far at least, is how well they seem to be working.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, the combined capacity of wind and solar energy in Morocco rose from just under 4% in 2009 to over 18% in 2020. If you include all renewables, that figure is closer to 30%. Where many governments around the world seem in danger of failing to meet their climate commitments within the brief time remaining to avoid the worst effects of climate change, Morocco stands out as an unlikely success story.

So why is Morocco going all in on renewables? And what can these reforms teach us about how to unlock the potential of clean energy in other countries? To answer these questions, I travelled to Morocco to interview local politicians, scientists, business leaders, members of parliament, and other energy transition stakeholders.

What I found was a delicate balancing act between institutional change, on the one hand, and political stability on the other. Effectively navigating demand for change and politics-as-usual will be key to the continued success of Morocco’s clean energy future.

The Institutions They Are a-Changin’

Tackling climate change requires a fundamental transformation in how our species produces and consumes energy, which in turn requires new institutions to incentivize a shift away from fossil fuels and toward renewables. The institutional reforms Morocco undertook after 2009 were pivotal in directing investment toward renewable energy using a variety of financial incentives.

For instance, the Moroccan Energy Investment Company provides debt and equity assistance for clean energy projects like the Jbel Lahdid wind farm currently under construction outside Essaouira. The Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy, a state-owned renewable energy company, both partially financed the construction of the Ouarzazate Solar Power Station – the world’s largest concentrated solar plant when it was built in 2016 – and issued guarantees to the project’s main investor, ACWA Power. Research and innovation grants awarded by the funding agency associated with the Moroccan Research Institute for Solar Energy and New Energy have supported over five dozen renewable projects.

Indeed, the success of Morocco’s reforms stems largely from the public financial institutions the country set up to direct investment flows into parts of the economy that generate value by reducing emissions.

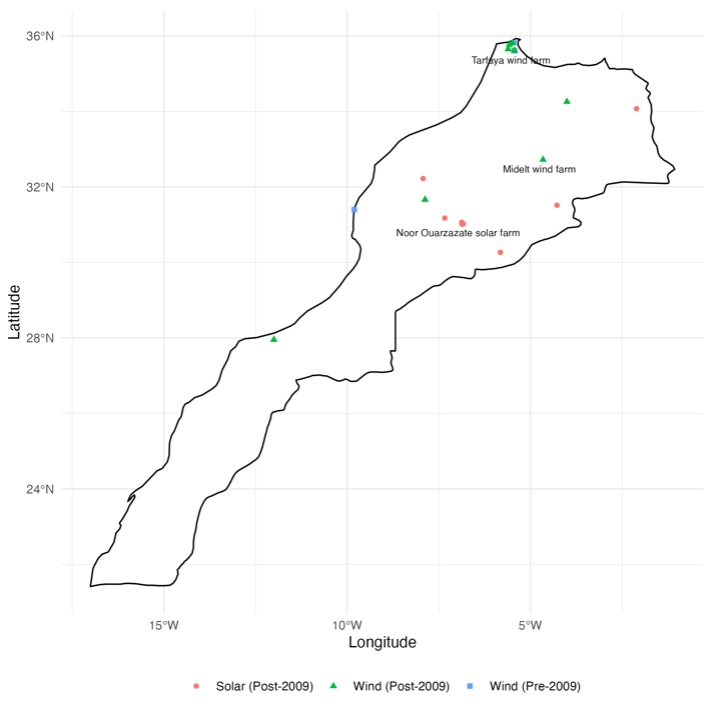

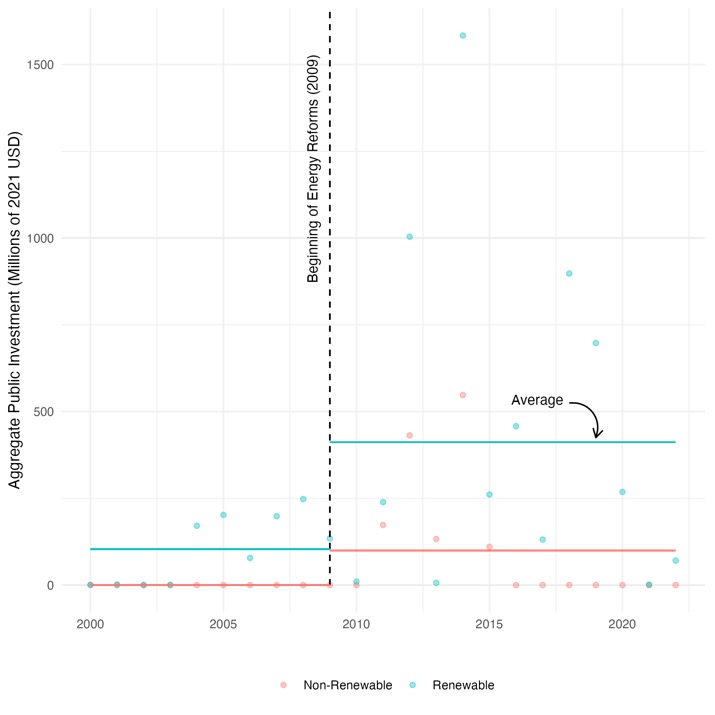

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of these public financial institutions. The left panel shows how the 2009 energy reforms led to a much larger increase in public investment in renewable energy compared to non-renewable energy. The right panel shows how almost all of the country’s wind and solar infrastructure was commissioned after 2009, thanks to these investments.

Figure 2: Renewable Energy Infrastructure and Public Investment in Morocco, before and after 2009. Source: Global Power Plant Database and International Renewable Energy Agency.

The More Things Change, the More They (Need To) Stay the Same

The founder of a wave energy startup in Tangier told me, “We’re trying to turn this place into the Wall Street of renewable energy.” That sentiment reflects the important role that investment has played in Morocco’s renewable energy reforms. The new institutions Morocco set up to promote renewable energy after 2009 are part of the country’s changing economic and political landscape. Paradoxically, however, these changes are taking place within the broader context of Morocco’s extremely stable political system.

What maintains this delicate balance between continuity and change in Morocco’s clean energy transition is the fact that the institutions it established after 2009 are backed by the power of Morocco’s royal family, a group of political elites that has controlled the country’s monarchy for 400 years. That’s real stability, according to a former cabinet minister: “Some dictatorships have a façade of stability, but not Morocco.” The cabinet minister I spoke with is not alone in his assessment, either. Every person I interviewed in Morocco told me that political stability helps explain why Morocco has been able to make more progress on clean energy than other countries in the region like Algeria and Tunisia. One renewable energy expert told me that, after a bombing in Egypt that occurred near a wind energy conference in 2011, international investors said on a conference call, “Morocco’s more stable; we’re going there” instead. Ironically, the kind of continuity-in-change that Morocco seems to have mastered may partially help answer the question of why some countries are better at transitioning to renewable energy than others.

However, stability also presents a risk of stagnation. While politics-as-usual helps attract investment, it makes things difficult to change if they aren’t working well. The main problem facing renewable energy in Morocco, according to a senior investment manager at a multilateral financial institution whom I spoke with, is the country’s inability to pass effective legislation implementing the kinds of regulations needed to make the country’s renewable energy investments as efficient as they need to be to achieve that 52% goal.

A Future of Opportunities and Challenges

A Future of Opportunities and Challenges

Morocco faces a mix of opportunities and challenges as it embarks on its renewable energy future. First, growing demand in Europe for renewable electricity produced in Morocco could help the country gain status over its geopolitical rivals. Morocco is home to the only grid interconnection between Europe and North Africa and is actively negotiating proposals to supply more renewable electricity to European markets. Moreover, the closure of the Mahgreb-Europe Gas Pipeline in November 2021 due to escalating tensions with neighboring Algeria means that Moroccan electricity could displace Algerian gas in overlapping market segments, like those in which utility companies phasing out coal.

Second, however, powerful fossil fuel interests still dominate much of the country’s political economy. The Prime Minister, Aziz Akhannouch, is also the CEO and majority stakeholder of Akwa Group – one of the country’s largest oil and gas companies. The discovery of large natural gas deposits off the Atlantic coast of Morocco last year further complicates matters by increasing the temptation to secure the country’s energy independence through expensive and environmentally devastating offshore drilling instead of continuing to build more wind and solar.

Figure 3: A Well in a City Square in Chefchaouen, Morocco’s “Blue City.” Chefchaouen’s mayor, Mohamed Sefiani, was listed as one of the 100 most influential people in climate policy in 2022-23 by the Apolitical Foundation. Source: Author.

Third, expanding renewable energy in Morocco comes with other environmental tradeoffs. For instance, Moroccan utilities use huge amounts of water to keep the country’s solar installations operating at peak capacity, but water availability is declining in response to a years-long drought exacerbated by climate change. As the world continues to experience both the accelerating impacts of climate change and a rapid transition of renewable energy at the same time, it will face new and potentially unforeseen challenges in environmental governance.