Comparative Study on the Antiquity, Monumentality and Design Principles Behind Batik Patterns Between Hmongb Rongt and Bouyei

Experiencing The World Fellowships

The summation of this research was to seek a solution to a current phenomenon in China. It is difficult to find authentic Chinese design in today’s design industry. Modern “Chinese” design is a superficial form claiming traditional philosophical inspiration. To which I ask, why? Is it that the ideology of traditional art is incompatible with a modern lifestyle? How can modern Chinese design gain inspiration from authentic traditional art by fusing its philosophical foundation with modern design? To address these questions is to observe the mechanism of an authentic traditional Chinese design such as Batik, a traditional wax-resistant dyeing technique mastered by the Miao ethnicity. This summer I visited fourteen villages in the Guizhou Province to execute an analysis of Miao Batik design.

The summation of this research was to seek a solution to a current phenomenon in China. It is difficult to find authentic Chinese design in today’s design industry. Modern “Chinese” design is a superficial form claiming traditional philosophical inspiration. To which I ask, why? Is it that the ideology of traditional art is incompatible with a modern lifestyle? How can modern Chinese design gain inspiration from authentic traditional art by fusing its philosophical foundation with modern design? To address these questions is to observe the mechanism of an authentic traditional Chinese design such as Batik, a traditional wax-resistant dyeing technique mastered by the Miao ethnicity. This summer I visited fourteen villages in the Guizhou Province to execute an analysis of Miao Batik design.

Miao and mountains

Miao is a joint name referring to small ethnic tribes in southwestern China who share similar ideologies and lifestyles with subtly different customs unique to their own tribes. The history of Miao is a history of migration. In ancient times, conflicts with stronger tribes compelled Miao people to settle in isolated mountainous areas. Additionally, due to Miao’s farming system, every few decades the whole tribe abandons its original land to begin the odyssey for new land. Choosing mountains proved advantageous, however, it rooted the introversion of Miao culture. High illiteracy of Mandarin further paralyzed Miao’s trading and cultural communication with Han society. These mountains not only nurtured Miao’s originality in culture, religion and politics, but also helped preserve Miao’s tradition from fast-paced infectious modern culture.

The function of Batik

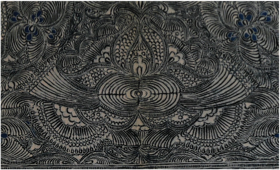

Batik stabilizes the society and provides a solution to their spiritual needs by acting as both a technique for traditional clothing and an educational tool to pass down Miao’s history and aesthetics. Although these Batik patterns may look outmoded and the associated myths may sound ridiculous, it is important to understand its origins. At Batik’s inception, a primitive stage of civilization, each pattern was a condensation of people’s emotions, thoughts and imaginations. Reproduction, a highly regarded worship, is associated with many elements and even compositions such as water whirls, fish, bird and Yin and Yang. Miao women incorporate everything organically into one piece. A great example is a baby basket from Zhijin. The basic unit can be seen as an embryo with bird’s head and fish’s tail. When they are connected, the new symmetrical shape visually suggests a bird or butterfly. Elements are repeated, rotated and combined to form a huge shape of Yin and Yang which implies fertility-the continuation of life.

Interviews with local scholars regarding the meaning of patterns always led to myths. When artisans found it difficult to articulate certain designs, myth was the medium which I used to coherently interact with them and dissolve the tension. Therefore, myths became the window through which I understood the correlation between Batik and Miao origin. Though I was not always able to exact the meanings of the patterns through myths, I still captured the flavorful remnant through their romanticized ancient folk songs.

Batik serves as a token of identity between members during migration, and also functions as a base stone for stabilization of Miao society. The quality of Batik, which suggests a girl’s intelligence, is closely associated with quality of marriage. Each year during the Miao dating festival, Batik, as evidence of a girl’s thoughts and effort, would be evaluated carefully. According to Xiong, though chained by established rules, a good Batik artisan should dance the wax pen freely on the cloth to create an exquisite context abundant in imagination.

Challenges

According to my original plan, I concentrated time and effort into exploring Miao and Bouyei tribes in Liuzhi and Anshun by conducting interviews with artisans. However, upon arrival in Anshun, I realized the authenticity of Batik was inundated in the wave of commercialization. Indeed, the rising Batik souvenir industry raises awareness by preserving Batik-making skill set. However, the tourist-oriented industry expose artisans to market need and public taste. Additionally, it is hard to tell whether government intervention is beneficial for Batik preservation. According to Professor Yang, the government invited artisans to study Western drawing skills, which led to implementing Western elements into traditional artwork. In the first three days, my interviews with artisans in the city proved ineffectual due to the aforementioned reason. Alongside a local driver, I began a three-week long journey seeking authentic Batik design in rural Guizhou and landed in Biasha, a small village.

Prior to the trip, I composed a questionnaire in Mandarin; however due to low literacy of the people I interviewed, I had difficulty in collecting substantial data. Growing up, Miao women are immersed in their local batik style. Such aesthetic isolation becomes double-edged sword; on one hand, the women can draw Batik patterns as easily as breathing, but they also have little knowledge of other styles and therefore cannot describe their local designs in comparison with others. To address this issue, a Miao translator utilized and prepared a series of pictures to assist the artisans in their explanations.

Looking Batik from Miao’s eye

Women are the keepers of Batik art. Miao girls, once reaching six years old begin Batik formal education with introduction to the names and meaning of Batik elements. The mother teaches the girl how to use a wax knife to draw simple patterns. When she reaches adult age, she becomes a true Miao artisan with the authentic rules of Batik melted in her blood. A finished piece usually consists of two colors: blue and white. A dark blue background emphasizes complicated lines drawn on the cloth. The complexity is increased by creating varying degrees of blue through waxing the cloth twice and through decorating colorful embroidery.

In Nayong, I finally encountered an artisan, Xiong, able to explain her work in Mandarin. The following is a description of her own work.

The composition is a symmetrical canvas separated into a bigger and smaller part by a band. In the bigger portion, two sunflowers, formed by concentric circles with stamen and petals radiating from the center, are drawn on each side. Xiong explained, from the perspective of a mountain top, the outer two layers resemble mildly curved expansive mountains. The lean triangles or petals represent pestles used to pound chili and grains. –

The triangular design in the center resembles a hanging bird. But actually there are three pairs of fish with simplified shape of shuttle, waving disproportionately big tails dismantled from the whole design. The symmetric concentric design at the very center could be comprehended as a fish viewed from left and right at the same time or as a pair of fish sharing one head. The curving dot at the center could be the eye and cheek.

A similar method appeared in other piece below too.

From the bigger picture, the whole piece can be interpreted as an aerial view of a jungle where the sun rises from the east and sets in the west or as an pool with fishes hidden under the leaves, or even a sky full of butterflies.

Leaves, butterflies and birds are suggested by the same leaf-shaped pattern filled with dense curves. In the small spaces left, she added a small pattern called belly of bird composed with cirrus to abstractedly characterize a bird silhouette. A series of bands with different thicknesses and patterns inside serve as boundaries between two different themes.

The roll pattern, according to her, was escargot as a snack of her childhood; the triangle represents the top of cedar, characteristics which Miao people admire; the oblique lines with dots at the bottom represent a spoon.

Based on this description, it is surprising that objects of different scales can be reduced to a same size and both serve the content. Contrastingly, a different artisan describes these bands as rivers flowing across the land, thereby providing a new perspective regarding the picture as a map of Miao’s original residential location. The pattern is similar to the Chinese character “正” which could represent the place where Miao ancestors resided.

However, Batik content does not solely correspond to one interpretation. Subtle balance of imagination and interpretation exist in almost every piece of Batik. For instance, Professor Yang counters that “正” is Yin and Yang.

Moreover, Xiong’s description of escargot and cedar seemed not to conform with the goal of Batik that is to connect with ancestors and strengthen admiration. Another distinct feature is their imagination. The pattern’s abstractedness creates space for interpretation. Xiong believes distinct dialects of Batik provide the first principles to help understand other Batik art forms.

Conclusion

The goal of this trip was to analyze how Batik solves a problem or fulfills the need of a society through investigating local usage and interviewing local artisans and professors.

Batik is a graphic art that is not limited to conventional forms of art. It is true that the composition of Batik sacrifices the rules of perspective, but the concept of seeing the magnificent from the trivial, the plurality from singularity can serve as a philosophical direction for Chinese design. Furthermore, the lack of uniformity of perspectives provides another possibility, that human beings are naturally comfortable with such cavalier perspective.

Finally, in a typical early morning of Guizhou, among Miao people from different tribes wearing Batik and wandering in temporal market downtown, one can feel the emotional bonds from the clothes they are wearing, that are made by mothers, sisters or themselves. As a design on the textile, its pattern, its meaning, its education and its developmental process unites one tribe. That power can never be replaced by texts and calls from cellphones and computers.