Research doesn’t happen only in musty archives or modern laboratories. Particularly at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies, students from a wide range of disciplines carry out research in locations around the globe.

Last summer, a Kellogg/Kroc Undergraduate Research Grant took fifth-year architecture student Carl Silliman ’13 to remote villages in Nepal, to the frenetic city of Kathmandu, and to impoverished Tibetan refugee camps in Mainpat, India. It was all part of a project in which Silliman teamed up with his faculty mentor to both research traditional Tibetan architecture and to apply its components and principles to a redesign of the Mainpat camps.

“My hope is that if our design becomes a reality,” Silliman says, “it can revitalize Mainpat. If we can create a sense of community architecturally, the refugee settlement will become a more livable and sustainable environment. It will feel more like a home to these Tibetan refugees.”

Reimagining Refugee Life

As Silliman explains, the Mainpat settlement consists of seven camps in a remote, mountainous region in central India. The Indian government established the camps in 1962 for Tibetans fleeing from the Chinese takeover of 1959. Now housing nearly 2,000 people who depend largely—and precariously—on farming for both daily food and trade, Mainpat has the lowest income and the most fragile infrastructure of all 37 Tibetan refugee camps in India.

[[{"fid":"4248","view_mode":"one_third_right","fields":{"format":"one_third_right","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"","field_folder[und]":"1215"},"type":"media","attributes":{"height":"225","width":"298","class":"media-element file-one-third-right"},"link_text":null}]]With no end to the refugees’ exile in sight, their spiritual leader, Tulku Tsori Rinpoche, is both reimagining and beginning to rebuild the camps.

Silliman learned of the Mainpat settlements through his mentor, Douglas Duany, professor of the practice in the School of Architecture. A leader in the New Urbanist movement, Duany has worked on several projects for the displaced in the Middle East.

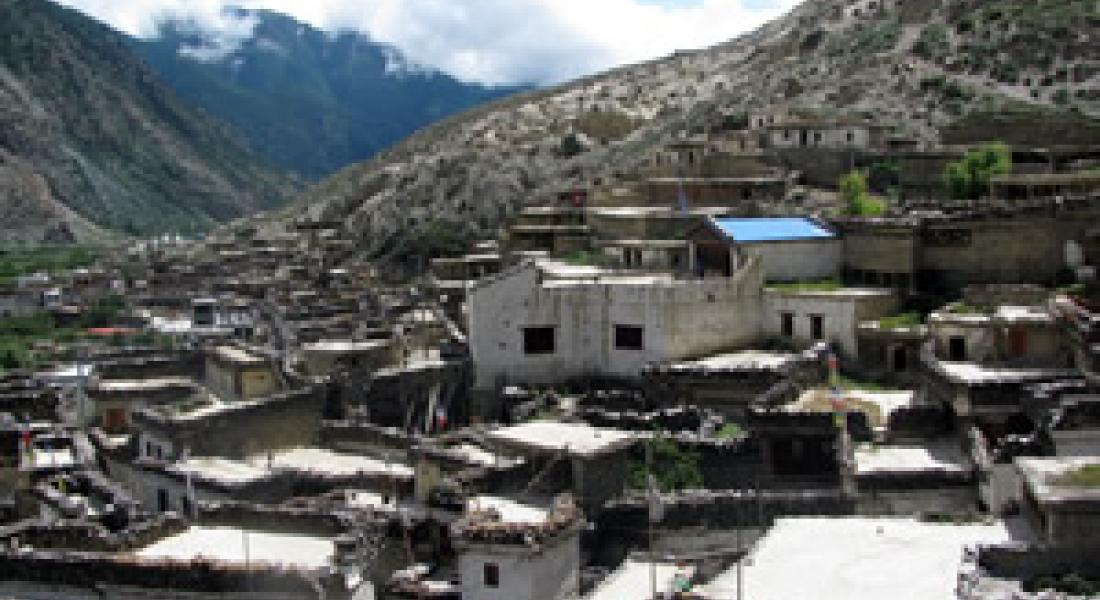

Having first studied villages in Nepal’s Upper Mustang region, where Tibetan settlements remain true to their residents’ design heritage, as well as the pedestrian-friendly city center of Kathmandu, Silliman recounts that seeing Mainpat for the first time was quite a shock.

“The streets [and mud brick homes] feel like Midwest American suburbia,” he says, “with no resemblance to traditional Tibetan towns.”

Moreover, after 60 years, the refugees’ homes are in severe disrepair. There are no real public spaces—only a few partially completed school buildings and a half-completed monastery, some even with rebar and concrete exposed.

[[{"fid":"4249","view_mode":"one_third_left","fields":{"format":"one_third_left","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"","field_folder[und]":"1215"},"type":"media","attributes":{"height":"225","width":"300","class":"media-element file-one-third-left"},"link_text":null}]]Silliman spent his two weeks in Mainpat immersing himself in both the realities of the settlement and the residents’ hopes and dreams. With his pattern book the Tibetan architecture of the Upper Mustang region, he filled three sketchbooks with drawings and ideas. As all architects must do, he took his cues from his client—the Rinpoche and the refugees.

Designing for Development and Sustainability

To revitalize the city, they are recreating it—both in terms of design and sustainability. Their vision includes new public buildings and public spaces—most prominently, a monastery/school and a marketplace.

The monastery/school will house 700 children—both those who live in Mainpat and some who would come from as far away as Nepal and Tibet. It will be a spiritual and educational beacon.

[[{"fid":"4250","view_mode":"one_third_right","fields":{"format":"one_third_right","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"","field_folder[und]":"1215"},"type":"media","attributes":{"height":"225","width":"300","class":"media-element file-one-third-right"},"link_text":null}]]The new center city market is critical to the Rinpoche’s strategy of replacing reliance on farming with the creation of new local products—for example, textiles. Silliman is designing the market as well as nearby workshops and housing.

Back on campus this year, he is translating his research and experiences into his senior thesis—an actual design to be presented this spring to the Rinpoche.

“I’ve been guided and inspired throughout my work by the realization that for the residents of Mainpat, as is true of all refugees, the home abandoned is the home desired the most,” Silliman says.

He is grateful to the Kellogg Institute for both the funding he received and assistance in procuring it.

“Coming up with the idea for a proposal is the student’s responsibility,” Silliman says, “but Kellogg is enormously helpful in shaping preliminary ideas. Associate Director Holly Rivers was also generous in advising me how to craft a complementary grant application to UNESCO, which cofunded my research.”

Earmarked for students after their junior year of studies who have the endorsement and pledge of supervision from a faculty member, last year’s Undergraduate Research Grants funded five undergraduates from a variety of disciplines. In addition to Silliman’s grant, funded projects ranged from the effectiveness of mosquito nets in Cambodia to the analysis of development indicators in Karnataka, India.