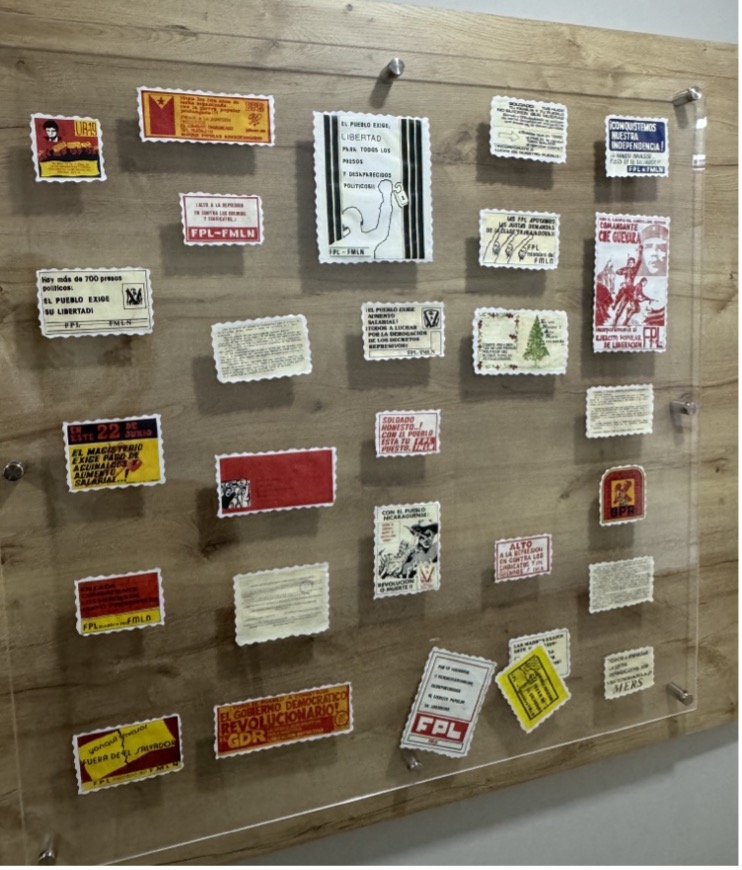

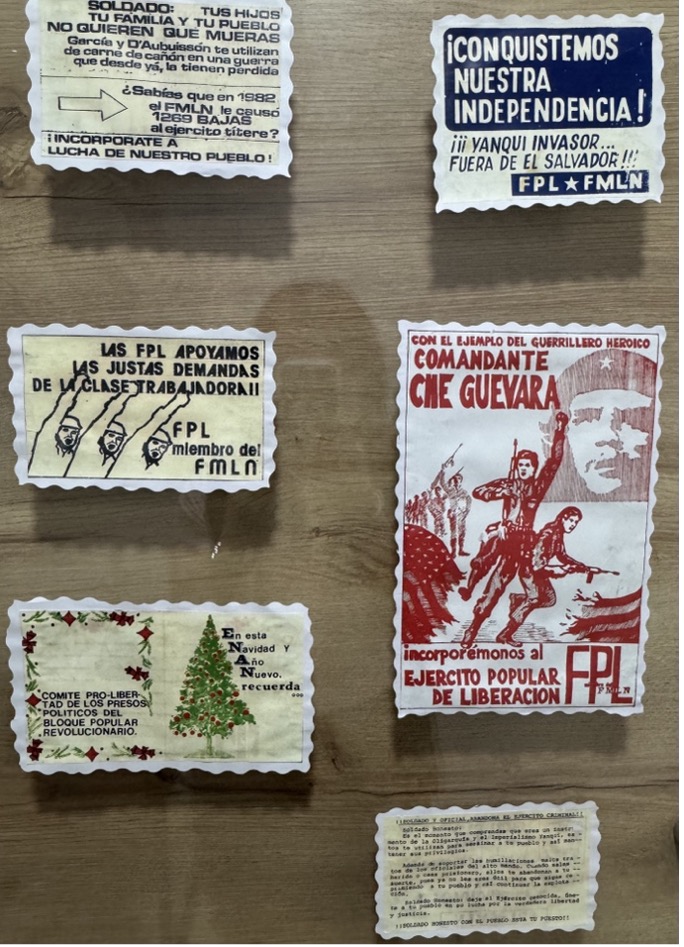

(Photo: Peace Negotiation Archives at Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica (CIRMA), Antigua, Guatemala)

In the 2024 Summer, Kellogg Doctoral Affiliate Isabel Güiza-Gómez (political science and peace studies) traveled to El Salvador and Guatemala on a Kellogg Institute Graduate Research Grant to conduct archival work and in-depth interviewing for her project “Landing Peace: Rural-Poor Mobilization and Land Redistribution in Civil War Peace Processes.”

Land reform has gained traction in civil war peace processes in the last decades. According to the PA-X Peace Agreements Dataset hosted at the University of Edinburgh, between 1990 and 2021, 42 out of 84 civil war negotiated settlements address land reform or rights, including land ownership, access to farming land and agricultural support services for the rural poor, and property returns. This trend runs counter to the conventional wisdom that predicts a trade-off between political incorporation of opposition actors and economic redistribution during political transitions. Why is land reform included in peace settlements and then implemented on the ground?

I develop and test a theory on how unarmed and armed opposition actors influence the negotiation and implementation of land redistribution in peace processes. Land reform is included in peace agreements when the opposition either poses credible threats to stability through class-based, belligerent collective action, or promotes consensus for reform via reparation-based, consensus-building mobilization. In the former scenario, rebel organizations and unarmed movements converge in their demands for land redistribution, employing combative strategies and framing land inequality as a fundamental issue of class struggle that underlies the armed conflict. In the latter, the opposition splits into factions where unarmed movements frame land grievances as reparations for outright injustices distinct from the war and builds alliances to forge broad-based support for reform. During the implementation phase, land delivery hinges on the systematic influence of newly incorporated opposition actors in policymaking, who benefit from new rights and routine access to state institutions.

My dissertation project addresses this puzzle through within-case and cross-case comparisons in Latin America, focusing on Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala. My primary focus is a comparative historical analysis of two major civil war peace processes in Colombia, a country with a significant history of land-related conflicts and numerous peace negotiations, making it ideal for theory building. In the first process (1982-2002), Indigenous and Afro-descendant movements secured communal land rights through reparations-based, consensus-building mobilization. In the second process (2012-2022), insurgents and peasants initially pressured elites into land reform commitments but struggled to ensure land allocation by deploying class-based, belligerent mobilization. Through a previous Kellogg research grant, I conducted intensive fieldwork in various municipalities in Colombia to collected archival data and carry out in-depth interviews and ethnographic work.

To evaluate the external validity of my argument, I conduct a shadow-case comparison of El Salvador and Guatemala, which serve as critical “most-similar” case studies due to shared background factors such as land inequality, civil war and authoritarian rule, and similar levels of state capacity. Although both peace settlements included land reform, the Salvadoran accord established property redistribution to landless former combatants and peasants, while the Guatemalan agreement relied on market-based allocation to Indigenous and peasant communities. Land was effectively redistributed to beneficiaries in the Salvadoran case, while land was allotted to a marginal extent in the Guatemalan case.

The Kellogg doctoral research grant funded extensive fieldwork in El Salvador and Guatemala in June and July 2024. My data collection includes original archives like insurgent, clandestine magazines, movement manifestos and newspapers, negotiation records, and footage of civil society meetings hosted by public libraries in San Salvador, Antigua, and Guatemala City. I also conducted 25 in-depth interviews with former insurgent negotiators, social movement representatives, and bureaucrats in both countries. Moreover, I collected official data on land allocation in the 10-year post-accord period for both cases.

Initial findings allow me to test the generalizability of my argument across other civil war peace processes in Latin America. El Salvador serves as a positive case wherein insurgents and social movement jointly compelled the government to compromise to redistribute land through the state reallocation of property rights from private and public land to landless beneficiaries. Opposition actors influence peace negotiation over economic reform by framing land inequality as a class struggle and credibly threatening political and economic stability. Newly incorporated opposition actors exerted systematic influence in land allocation, leveraging their novel access to state institutions.

In contrast, Guatemala represents a negative case in which insurgents lacked the capacity to extract costly concessions from the government. While social movements sought to foster broad-based consensus for land redistribution by detaching land grievances form war dynamics, they were only able to force the government to compromise on market-based land reform rather than state-led redistribution. In the post-accord period, elites effectively disincorporated opposition actors from policymaking, using their institutional control to hinder the implementation of land reform.