Cognitive Barriers to Accessing Healthcare for People with Intellectual Disabilities in India

Kellogg/Kroc Undergraduate Research Grants

Summer 2018

Cognitive Barriers Faced by Caregivers of People with Intellectual Disabilities in India

Living eight weeks in India is bound to come with a few surprises. I walked in not expecting everything to go as planned, but little did I know how true these words would become. The purpose of my trip to India this year was to understand the cognitive barriers that caregivers of people with intellectual disabilities face in India. The three types of caregivers I targeted were medical professionals, organization workers, and primary caregivers such as parents. Another goal of my project was to do a comparative analysis between two different states in India with vastly different levels of subnationalism, which is essentially one’s affinity for the state they are in. I spent one month in Kozhikode, Kerala and another in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh.

I remember how relieved and happy I was when I saw the sign for the Composite Regional Center (CRC) in Kozhikode; the place actually existed! A part of me was worried that once I got to the city things would not work out and I would be scrambling to pull a project together. Fortunately, most of my worries were dispelled the day I met the director. He welcomed me in with kindness and support. Not only did he give me full access to observe and speak with his staff, he also connected me to other institutes nearby. However, at the end of my first week, I became aware of the Nipah virus, which had already killed a few people. The Nipah outbreak ultimately prevented me from visiting the Medical College campus that was down the road as it was the treatment site for those affected by the virus. In the beginning I was not too concerned, but as the following week went by and more people started succumbing to the disease, I became worried. Despite this, I was assured by the professionals around me that the risk of contracting the virus was quite low, as I did not have any contact with the infected patients. The government’s quick and precautionary actions prevented a wide outbreak of the virus and I left unharmed. However, due to the virus, the government had postponed the opening of schools and no patients were coming to the CRC. I was only able to interview professionals from the CRC and the Institute of Mental Health and Neuroscience (IMHANS), which shared the same building.

Through my interactions with professionals in Kozhikode, I began to build a picture of the experience of a person with intellectual disability (PWID) in India and specifically in the state of Kerala. I also began to understand the lived experiences of those who take care of PWID. Much of the treatment process is focused on rehabilitation as opposed to medical treatment. It is through therapy that children and adults can see significant changes over a consistent period of treatment. Although the CRC in Kerala has only been operational for a few years, it is already setting an example for other CRCs on how to increase awareness and provide better support for families. IMHANS and CRC-Kozhikode try their best to use a multidisciplinary approach in the care of their patients. There are a few constraints to this that include lack of personnel, overflow of patients, and limited time. Despite this, both centers are trying their best to increase the quality of services they provide to their patients.

One of the most memorable experiences I had in Kozhikode, was when I sat down with a mother of a child with intellectual disability and spent two hours listening to her journey with her daughter. As she recounted her joys and sorrows I could see the emotion written on her face and I could not help but be in gratitude for her willingness to share with me. After having conducted many interviews where personal emotion had not been expressed, I realized how impactful it could be. It is a privilege to be in a space where someone is willing to take the time to share their experiences and perspectives with you.

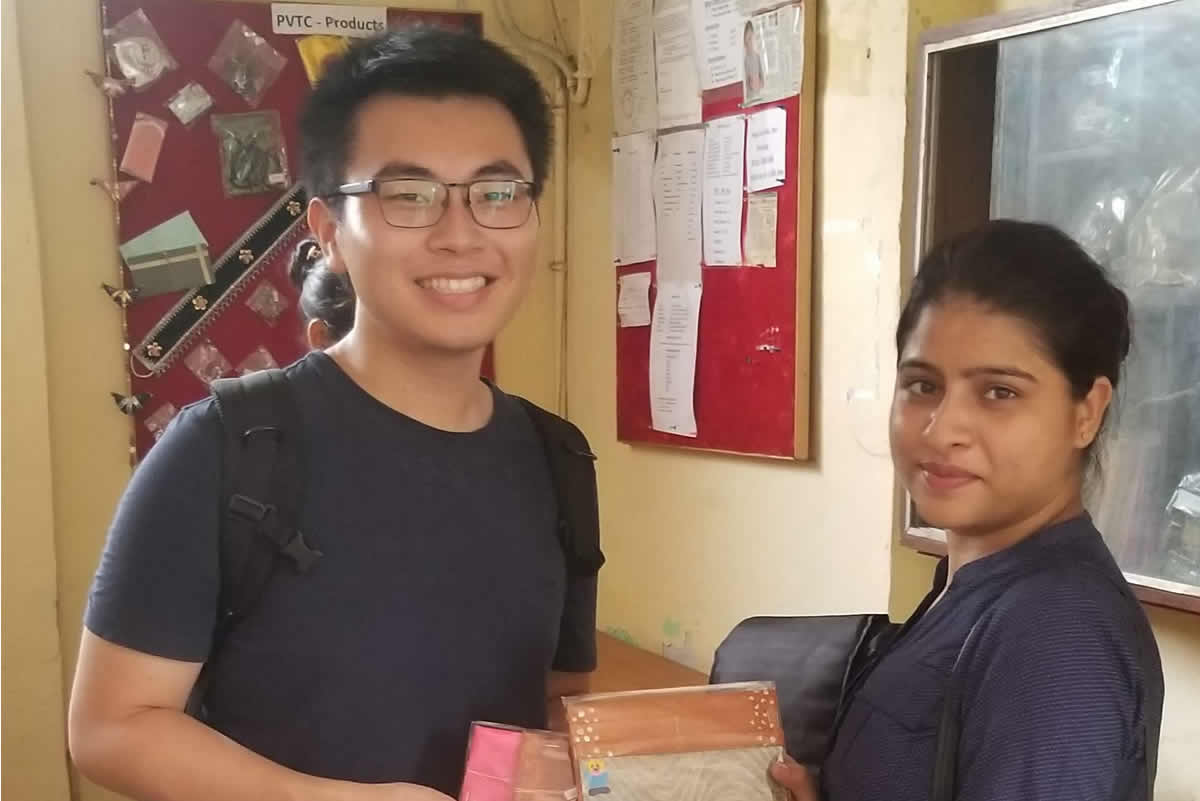

The biggest administrative challenge I faced during my eight weeks was when I tried to secure an internship at the Composite Regional Center in Lucknow, the second city in which I conducted research. After waiting two weeks for the director to come back, I was still not granted permission to interview staff members. At the end of the month, my request had gone to the Ministry of Home Affairs, which I certainly did not expect. Although I was never granted permission at the CRC in Lucknow, I was connected with many other NGOs where I had the opportunity to speak to various professionals and parents. Being able to visit different NGOs gave me a broad sense of how organizations build homes and schools to care for children with intellectual disabilities. On a more challenging note, one of the most difficult things I had to listen to was when a mother described how her husband and family treated her child. The child was told that they were useless and should not be let out of the house. Extended family and their own community did not accept the child nor understand their capacity to love and be loved. On a lighter note, almost all the organizations I visited were truly doing great work with children with intellectual disabilities.

Conducting research this summer certainly taught me a few lessons. One of which was the simple fact that the direction and fruit of my research was largely dependent on how often I reached out to others. The balance between being persistent and allowing time for a person to respond was tested this summer, as there were multiple times where I felt I waited too long and should have been more direct with my requests. India has a great culture of welcoming guests and treating them kindly. Throughout my two months in India, individuals would extend their willingness to share and talk with me time and time again. I continue to be humbled and grateful for the hospitality shown to me.

My experiences in Kerala and Lucknow were quite different. In the end, I managed to interview the three types of caregivers I set out to speak with, but I was not able to do a comparative analysis between the two CRCs. In terms of a political comparison between Kerala and Uttar Pradesh on the basis of subnationalism, there seems to be a significant difference between the way citizens talk about their own state in Kerala than in Uttar Pradesh. People in Kerala more heavily identified themselves with positive aspects of the state than compared to those in Uttar Pradesh. Upon further examination of the data, there are three topics that stick out to me: family, government, and professional caregivers. Due to the unexpected circumstances in both cities, the data that I have collected covers a wide range of topics and, after speaking with my advisor, I will be looking at the demographic portion of the interview and seeing if that in some way affects the result of a person’s experiences with a professional, organization or the government. Beyond this I am looking at potential ways different organizations affect a person’s experience whether as a medical professional, organizational worker, or primary caregiver. In Kozhikode, I only worked with governmental organizations and most of the people I interviewed were professionals. I was only able to interview a handful of parents. In Lucknow, I mainly worked with NGOs and interviewed organization workers and parents. I originally proposed to look into the cognitive barriers within the caregivers of PWID and am now looking to find a connection between the two cities that is unrelated to their difference in geography. I hope to use this research to inform the organizations I visited on the barriers, whether, cognitive, social, or cultural, that exist within relationships between parents, medical professionals, organization workers and the government.

Adviser: Susan Ostermann