Exploring Mental Health Programs in Nepal

Experiencing the World Fellowships

Adviser: Gerald Haeffel

Final Report:

My eight weeks in Nepal were spent partnering with the NGO KOSHISH - Nepal's National Mental Health Self-help Organization. My first research objective was to use US-validated cognitive measures translated into Nepali to evaluate KOSHISH programs’ effectiveness. Second, I hoped to use my data from these surveys to evaluate if the cognitive measures used (Cognitive Style Questionnaire, CSQ; and Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire, MASQ) are cross-culturally valid and reliable.

I spent my first few weeks in Nepal getting acquainted with my organization and the different facets of their Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) outreach programs. I spent a week in the transit home, getting to know the women they serve. KOSHISH programs primarily serve female victims of domestic and gender-based violence. Many have been chained up in their homes or abandoned by their families in the streets. My understanding of the prevalence of violence against women in Nepal is that it is due to the lack of acknowledgment that this is a problem, and the lack of awareness about mental wellbeing and mental health problems was deepened. I had read statistics from the World Health Organization and from KOSHISH publications, but the reality of meeting Nepali women with broken limbs from their spouses brings the matter to life.

Due to having less cooperation than envisioned from the transit home workers with my research plan, and the lack of available bilingual staff, I shifted my research focus to the other CBR program in my proposed research plan: the self-help therapy groups. KOSHISH has ten functioning self-help therapy groups throughout the Kathmandu Valley. I organized field research trips to five of the groups. It was challenging to even set up these trips for multiple reasons. First, most of the therapy groups required two to three hours of bus transportation, including switching bus lines, so I was unable to travel independently. Second, I needed the assistance of two bilingual psychology student interns to assist with translation for my research; their schedules did not always coincide with the meeting dates of the self-help therapy groups. Finally, even when I did have a plan in place, the staff members scheduled to meet me for transportation would, at times, not show up at all with no communication of a change in plans. My research project helped me learn how best to self-advocate in a different culture’s workplace while still respecting their authority and superior knowledge of their region and programs. My field research in the self-help therapy groups was my favorite part of my partnership with KOSHISH.

In Lele, Lalitpur, we reached the health post where the therapy group meets after a two-hour bus ride. The diversity of the self-help therapy group participants varied day to day. In Lele there was only one younger person and one much older person. There were not many members with officially diagnosed mental disorders because many of these people have not seen a psychiatric doctor for their issues, and no licensed medical professional (clinical psychologist or psychiatrist) leads these self-help therapy sessions.

In Old Thimi, Bhaktapur, the therapy site was much different than the health center. We met inside a Buddhist Stupa, and all sat together on floor mats. I felt people shared more openly with fewer interruptions between the therapy group participants. There was a participant who was asked about her family members, which triggered a convulsive attack of emotion. It was concerning that someone suffering from such intense emotional trauma and mental instability could be receiving as little care as a therapy session once a month, not conducted by a licensed professional.

In Old Thimi, Bhaktapur, the therapy site was much different than the health center. We met inside a Buddhist Stupa, and all sat together on floor mats. I felt people shared more openly with fewer interruptions between the therapy group participants. There was a participant who was asked about her family members, which triggered a convulsive attack of emotion. It was concerning that someone suffering from such intense emotional trauma and mental instability could be receiving as little care as a therapy session once a month, not conducted by a licensed professional.

I had mixed opinions in response to the self-help therapy groups. While the locations for group meetings were not always therapeutic and there was minimal consistency/organization that would lead to standardized therapy, the majority of people seemed very comfortable to share in this setting and many expressed their gratitude to KOSHISH and gratitude for this space to talk about things they cannot discuss at home or to anyone else. These were heartening sentiments.

My preliminary research analysis showed that the KOSHISH self-help group CSQ average, 4.52, was higher than the US non-clinical sample average, 4.0, and a Honduran sample from an orphanage, 3.4 (the higher the number = the greater cognitive vulnerability to mental illnesses like depression). The difference in averages is a subject that requires further analysis, but some sources could be a different cultural paradigm for causes of mental health problems or different understanding of the question prompts. The results were normally distributed, as they would be in a native English-speaking sample, which confirms that the Nepali translation of the CSQ cognitive measure is cross-culturally valid and reliable. This finding fulfilled one of my central research objectives. Throughout this research process I learned how to organize and run an independent research project with little on-site professional support; how to establish rapport and conduct research across a language barrier; how to speak some basic Nepali; and how to represent myself in a Nepali workplace with a different culture.

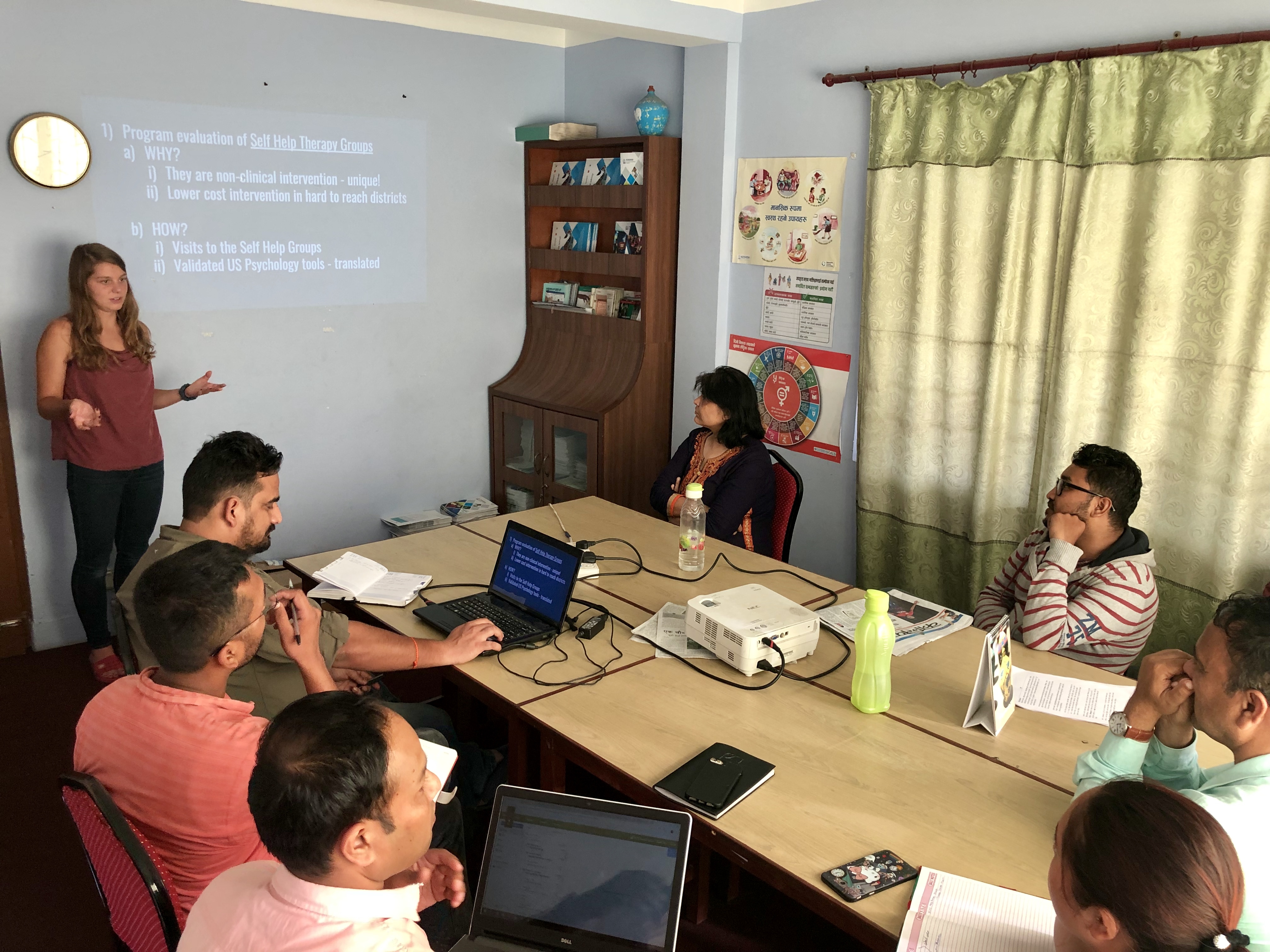

The most rewarding moment of my work with KOSHISH occurred during my final research presentation during my last few days in Nepal. In my final presentation, I explained how the results of the CSQ and MASQ (cognitive measures) were distributed normally, as they would be in a native English-speaking sample and how this meant the Nepali translation of the measures could safely be used in future research. The head of program development at KOSHISH was extremely excited about the results and asked to make sure I send him the most recent Nepali translation of the cognitive measures in order for KOSHISH to use the tools in the future. He even mentioned potentially continuing my research as a longitudinal study. I did not come to KOSHISH hoping to make a huge difference or change anyone’s lives, but I do feel relieved that my research can offer the organization tools for their own use and development in the future.

Overall, my time in Nepal opened my eyes to the still-present need for education to raise awareness about mental health and associated problems in rural, developing areas. I witnessed many hopeful steps toward change and helped develop grant proposals, inching KOSHISH closer to even more beneficial mental health outreach programs. However, there is still much work to be done until all people in Nepal, and worldwide, can openly discuss their mental health and seek accessible treatment. I look forward to continuing research on self-help therapy groups’ efficacy as low cost, non-clinical interventions more easily made accessible to populations in areas without well developed psychiatric care.