How do you plan and write a dissertation when the world is shutting down?

When you’re under lockdown and you can’t travel to do your field research?

When the projects critical to your work – really, to your career and your future – have been halted?

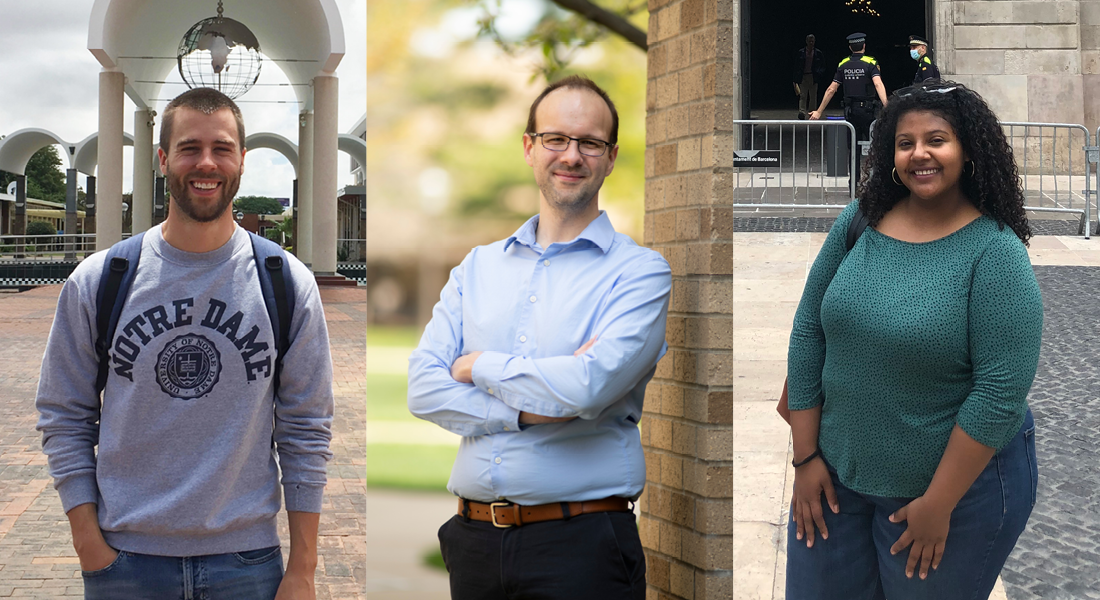

Last spring, the coronavirus forced PhD students around the world to make quick decisions about whether to stay or go, pull the plug on research critical to their dissertations, or take their projects in entirely different directions. The challenges were compounded for many of those connected to the Kellogg Institute for International Studies because of the global nature of their work.

Three Kellogg-affiliated doctoral students, all comparative political scientists and all working far from home when the pandemic hit, spoke about how COVID has affected their lives and their work in the past year. These are their stories.

Paul Friesen

Dissertation: “Democratic Enculturation: Explaining African Dominant Party Systems”

“We didn’t know how bad the pandemic was going to be, and almost overnight it seemed that we would be stuck in Zimbabwe because there were virtually no flights out. And that would mean my wife would have her baby there.”

They knew COVID was coming. They just didn’t know how quickly it would turn their lives upside down.

After spending several months in Botswana, PhD Fellow Paul Friesen and his wife arrived in Zimbabwe in January 2020. They expected to spend the spring there while he conducted the second half of his fieldwork for his dissertation, which examines the historical and cultural context behind why Africans support certain political parties.

Early in their stay, they began hearing more and more about COVID. Friesen, worried that an outbreak could eventually halt his research – a public opinion survey that asked questions related to religion, culture, and politics – tried to fast-track it.

In the meantime, they left the capital of Harare in March for a short vacation and had no internet access for several days. When they finally went to a restaurant where they were able to check their email, Friesen was bombarded with messages, many of them from the University of Notre Dame and the US State Department.

COVID, it seemed, had exploded overnight. They needed to decide immediately if they were going to return to the United States, even though doing so would mean walking away from his research and putting his timeline for graduation at risk.

There was another complicating factor – Friesen’s wife was several months pregnant with their first child.

“At this point we were panicking,” Friesen said. “We didn’t know how bad the pandemic was going to be, and almost overnight it seemed that we would be stuck in Zimbabwe because there were virtually no flights out. And that would mean my wife would have her baby there.”

Friesen’s project was soon canceled due to the coronavirus; he had missed finishing the survey by several weeks. But he still struggled with whether he should leave Zimbabwe immediately with his wife. Or, should he stay behind after she left and help in a country that, through his years of research there, he had come to love? Doing so would mean he could potentially get stranded there for months and miss the birth of their daughter.

“Even after I knew my research for sure was not going to happen, I felt like I was abandoning my friends and community in Zimbabwe. It’s not a country that has handled past health crises very well, and I wanted to do something to support this community that I cared about,” he said.

“Even after I knew my research for sure was not going to happen, I felt like I was abandoning my friends and community in Zimbabwe. It’s not a country that has handled past health crises very well, and I wanted to do something to support this community that I cared about,” he said.

The couple ultimately decided to leave together; Friesen, after talking the matter over with a mentor, realized there wouldn’t be much he could do to help during a pandemic. They left Zimbabwe a week later.

“There was almost an exodus of expats trying to get back to their home countries before the pandemic got really bad, and we were paranoid that our flight would be canceled,” he recalled. “By the time we got home, we were a little shell-shocked, but happy to be home.”

From Indiana, Friesen continued teaching a course at the University of Zimbabwe that went virtual, even though it was difficult for students to watch the classes online because of the cost.

The couple welcomed a healthy baby daughter several months after their return, and Friesen will return to Zimbabwe this summer and expects his survey to be done in the coming months. Because his research was postponed, he will defend his dissertation a year later than expected. He will receive financial backing from the Department of Political Science as well as a Kellogg Dissertation Year Fellowship during his final year.

The delay has allowed him to work on other projects and incorporate new readings and data into his work – all of which have made it “a little bit richer,” he said.

“In some ways it’s been good to slow down,” he said. “If you do comparative politics, the five-year time frame can be really brutal, and I think everything will be a higher quality in the end because of the delay.”

Benjamin Garcia-Holgado

Dissertation: “Populism and Democratic Erosion in Latin America”

“I will be forever grateful to them because they showed an extreme level of resilience, of adaptability, of trying to learn in this uncomfortable situation of being six feet apart and wearing masks."

PhD Fellow Benjamin Garcia-Holgado planned to defend his dissertation proposal in May 2020 and then travel to Venezuela for six months of fieldwork. But with COVID, his proposal was postponed and the trip never happened.

Instead, he spent the fall semester in a Notre Dame hotel ballroom, teaching an undergraduate class amidst the uncertainty of spiking COVID cases on campus and fear for his own family half a world away.

“It was a scary time,” said Holgado, who studies the role of independent judiciaries in limiting populist reforms in Latin America.

His research relies heavily on interviews with political elites in South America, including in countries like Venezuela where phone and internet connections are weak and making face-to-face connections is critical to establishing trust.

With his trip to Venezuela canceled, Holgado turned to teaching – something he had hoped to do eventually, just not so soon.

His undergrad-level “Global Populism and the Future of Democracy” course met in a ballroom of the Morris Inn to comply with social distancing requirements. There were plenty of logistical issues: In-person classes were temporarily suspended at the beginning of the semester due to a rise in COVID cases on campus. Some students came down with the virus, while others were quarantined due to COVID exposure. And on top of that, distancing and mask-wearing made it hard for the instructor and 27 students to even hear one another.

Still, Holgado found the experience inspiring because of the students.

“I will be forever grateful to them because they showed an extreme level of resilience, of adaptability, of trying to learn in this uncomfortable situation of being six feet apart and wearing masks,” he said, adding that it gave him valuable teaching experience that will help him on the job market.

Since then, Holgado has moved forward with his dissertation, though COVID has limited him to research he can do virtually. Until he can travel, he’s concentrating the bulk of his research on Argentina, the most developed country in his study. Weak internet connections in his other target countries of Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia make it difficult to do interviews remotely, or even to access materials like newspaper articles online.

Since October 2020, he’s conducted more than 60 interviews with Argentine political elites – politicians, judges, journalists, and criminal lawyers – via Zoom, as well as a few by email, phone, and WhatsApp. But he’s learned that virtual interviewing has its limits. Nearly two dozen people have declined Holgado’s interview requests because they will only meet with him in person – probably, Holgado believes, because they’re worried about being recorded.

The delays to his research mean he will likely graduate in six years instead of five, but he said his advisors at Notre Dame have been understanding of his predicament.

“One important reason I chose to come to Notre Dame for my PhD is I always felt very supported by everyone here, and that was true of the political science department and Kellogg before and during COVID,” he said. In one instance, Kellogg staff jumped in to help when he had connectivity issues at home and feared he would have to cancel his Zoom interviews. Instead, they booked a room for him in the Kellogg office so he could do the interviews as planned.

“It’s a minor thing but it gave me peace of mind,” he said. “I was already nervous about doing the interviews by Zoom, but I knew I could go there and it reduced uncertainty.

“Now, I’m 100 percent focused on my dissertation.”

Andrea Peña-Vasquez

Dissertation: “Between the Patrón & the Padrón: The Local Dimensions of Legal Status in Spain”

“Honestly, I think the balcony helped me keep my sanity. Not only did it help me feel solidarity with my neighbors every evening when we’d clap for the healthcare workers, but it also helped me feel not trapped in my apartment."

Andrea Peña-Vasquez has a secret to surviving lockdown: her balcony.

The doctoral student affiliate was living in Barcelona and conducting fieldwork for her dissertation when the pandemic began. In hard-hit Spain, strict COVID restrictions meant that, early in the crisis, she could rarely leave her apartment without risking a fine.

“At first, you could only go to the grocery store or walk your dog if you had one. If you didn’t have a dog or a bag for food, you could get stopped by the police,” she said.

Her narrow, wrought-iron balcony overlooked an alley in central Barcelona, where she shared an apartment with her roommate, and gave her a window to the world.

“Honestly, I think the balcony helped me keep my sanity. Not only did it help me feel solidarity with my neighbors every evening when we’d clap for the healthcare workers, but it also helped me feel not trapped in my apartment,” she said. “I could see and feel the sun and be outside without breaking the rules.”

Peña-Vasquez had been in Spain for a year and a half to work on her dissertation, which evaluates a social settlement program in Spain that allows undocumented people to gain legal status after they’ve lived in the country for three years. Her work focuses on immigrants from Mali.

Peña-Vasquez had been in Spain for a year and a half to work on her dissertation, which evaluates a social settlement program in Spain that allows undocumented people to gain legal status after they’ve lived in the country for three years. Her work focuses on immigrants from Mali.

While she could have flown back to the US at the start of the pandemic, before a travel ban was put in place, she chose to stay.

“It was somewhat scary because I didn’t know if I should return early or wait. If I waited, I had no idea when it would be safe to return without putting my parents at risk,” Peña-Vasquez said. She worried about catching COVID in a crowded airport if she flew back. And, despite the rapidly rising case numbers in Spain, she saw Spaniards willingly comply with the lockdown – something she suspected wouldn’t have been the case in the US.

“In many ways I felt safer in Spain, and that was part of the reason I stayed,” she said. “Looking back, that was the best choice for me.”

Peña-Vasquez had a network of friends and activities in place that she maintained through lockdown. Her boxing classes moved to Zoom – “ironically, I was in the best shape of my life because there was nothing else for me to do,” she joked – and students at the institute she was affiliated with in Spain met virtually to discuss shared readings and to socialize.

The pandemic also gave her the chance to take part in virtual Kellogg events, like works-in-progress and the Comparative Politics Workshop.

“Those are things I wasn’t able to do before COVID, and it was nice to be reintroduced to the Kellogg community before I came back to the US,” she said.

The pandemic halted Peña-Vasquez’ fieldwork. Last spring, she had planned to interview municipal officials at two case sites where she had previously interviewed immigrants. But she couldn’t leave her apartment, and doing phone or Zoom interviews wasn’t a realistic option.

“Spanish bureaucrats are not well-known for answering phones,” she said. “It’s very hard to get on the line with somebody, and that was my experience even when I was in Spain. You have to talk to somebody in person.”

She said the limitations posed by COVID forced her to be more creative with her dissertation and turn to online newspaper accounts and secondary data like public statements from public officials. But she knows she’s lucky: she finished most of her data collection before COVID and is on track to graduate on time.

But the stress of the pandemic has impacted everyone, she said.

“It’s just overwhelming to be expected to maintain the same level of productivity we had before the pandemic,” she said. “A lot of people are like, ‘Well, it’s been a year. It’s something you should be used to by now.’ But it’s not something you can get used to.”