Exploring the Institutional Origins of African Partisanship and Political Ideology

Graduate Research Grant

My dissertation will focus on developing a more comprehensive understanding of party system outcomes and political ideology in Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition to more elite-based explanations of ruling party dominance such as the leveraging of resource rents for patronage networks and the application state coercion against political opponents, my research seeks to highlight the importance of partisan support, even in the face of stagnant economic growth and democratic disappointments. I argue for a more generalized interpretation of political ideology and partisanship that incorporates key values and ideals that can be tested and compared across countries with different historical context and development levels.

REPORT - October 1, 2018

The purpose of this grant was to provide a stepping stone for future dissertation fieldwork by allowing me to travel to each of my cases study countries. My dissertation focuses on developing a more comprehensive understanding of party systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. The viability and support for political parties is determined by a range of factors that must be tracked and analyzed over time. Historically, the African politics literature has focused heavily elite-explanations for explaining essential changes and patterns of political development and regime change. The most useful body of analyses around political competition and democratic development on the continent have been case study projects. Obtaining a solid understanding around the variations in political party strength, levels of electoral competition, and bases of political mobilization is vital in order to grasp a more informed picture of democratic trajectories in the region.

The ultimate goal of this project is to development a continent-wide explanation for why countries have developed into institutionalized competitive party systems, institutionalized dominant party systems, or non-institutionalized party systems. This is most directly informed in our current context by the success or failure of the inaugural ruling, and is thus a chief focus of the project. This central variable of inaugural party rule is what informs my case study selection. While the historical analysis of my dissertation will be continent-wide, I will also conduct fieldwork in four countries that are English-speaking, former British colonies, and critically, have demonstrated a great deal of variation on the dependent variable. These included Ghana, Zambia, Botswana and Zimbabwe, the latter three of which I travelled to under this research grant. Below I detail my activates in these three countries as well as some of the most important theoretical takeaways.

Harare, Zimbabwe (September 11-18)

During my visit to Harare, I was able to arrange eight meetings to discuss my research topics, ask specific questions about Zimbabwean history, and gain an improved understanding of the current political context. Two of these meetings were with University of Zimbabwe professors who are both well known in the academic and policy/NGO communities. I will be seeking institutional support from the University of Zimbabwe in order to receive a research permit and so these connections are extremely beneficial. In addition to these professors, I also met with two other experts that have received PhDs in political science, one at the Canadian Embassy and the other working for an international NGO. This group of academic-focused individuals were able to guide me through some of the crucial historical context and theoretical arguments. I also gained an incredibly in-depth perspective on recent political events by meeting with a former MP, a human rights lawyer and activist as well as the country director and elections officer at the NDI Zimbabwe office. Overall, I was very pleased with both the scope and quality of these interviews.

Lusaka, Zambia (September 18-25)

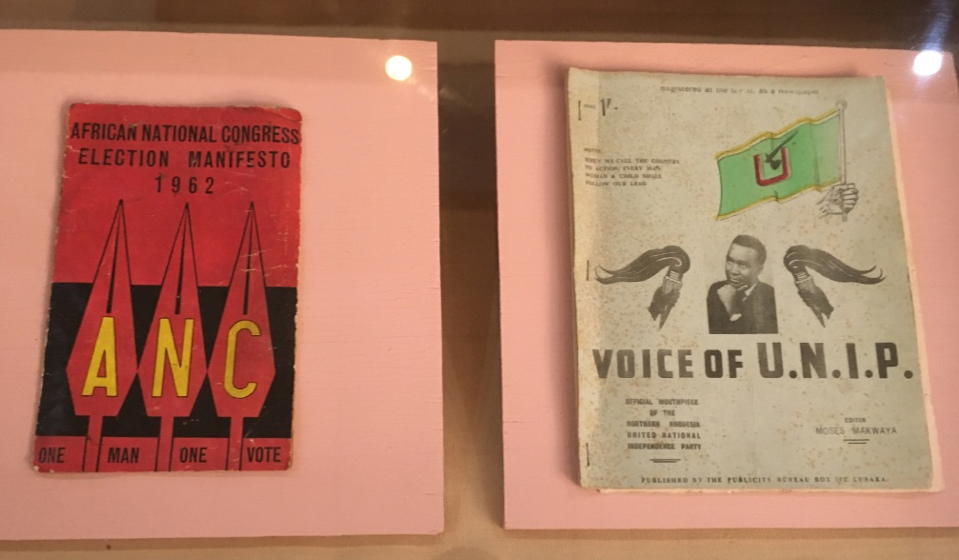

In Lusaka I was able to conduct seven meetings, five of which were with staff from the University of Zambia. Initially I had a long and productive conservation with one of my former NDI supervisors who not only provided with current political context, but was also very helpful in providing other contacts. One of these was a well-known political figure from the MMD political party, who was at the front of pushing for the reintroduction of multi-party democracy in the 1990s. This former politician and traditional leader provided me with an interesting counter-narrative around decolonization and the first party in power, UNIP. The remaining interviews were with academics from the University of Zambia, four from the political administration department and one from the law school. Two of these interviews were with older scholars who were especially helpful in filling in some of the details and complexities of Zambian political history from around 1950 to 1990. I was also able to make contact with some of the individuals who serve as V-Dem coders for Zambia at the university.

Gaborone, Botswana (September 25-30)

My time in Gaborone was only five days and included a holiday weekend as I overlapped with their Independence day. Because of this I was not able to secure every meeting I was hoping for, but did complete five while in country. My first was with a political expert and activist who providing me with wonderful answers to someone of my most difficult questions. Through a mutual contact, I was also able to sit down with two officers from the political desk at the U.S. Embassy, where we discussed both past and present politics in Botswana. Through these meetings I also received a contact at the university. Thus, I also met with two political science professors at the University of Botswana. I was encouraged by their interest in my project and welcoming my request to receive institutional affiliation in the future.

Outcomes

Overall, I am quite content with the quantity and quality of these interviews and information. The trip was crucial for laying the groundwork for both an improved dissertation prospectus as well as building my professional networks ahead of fieldwork next year. While the discussions were wide-ranging, I would like to highlight some of the most prominent knowledge gaps I was able to improve on. First, I have gained a much stronger grasp around the complex interactions of ethnicity and politics in each country. Most critical was understanding where and why ethnicity has been important to voters and how clearly ethnic identities are aligned with certain parties. Second, I improved my knowledge of how colonial conditions influenced the nature of national liberation movements, and how African leaders attempted to leverage these sentiments with varying degrees of success. A relative constant in my discussions was the role of patronage as a tool for political party entrenchment, though the dimensions and avenues of this range greatly from country to country. Finally, another major theme in all three countries (in particular Botswana and Zimbabwe) was the growing political divide between younger and older generations. This is driven not only by an increasing socio-political split among the urban and rural populations combined with increased levels of education, but the growing distance in time between an individuals’ personal experiences and important political events, all of which inform different rationales for voting and party support.